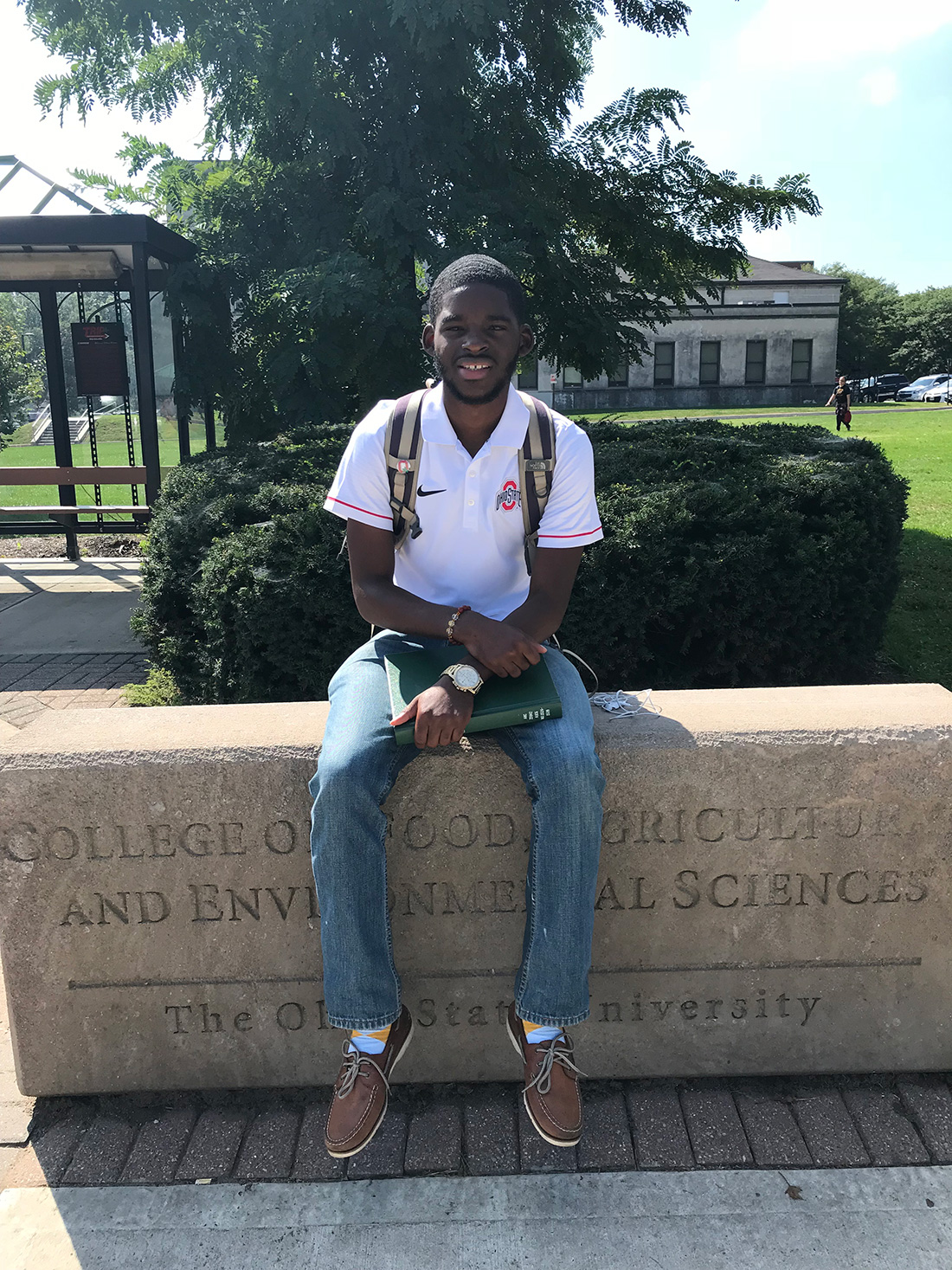

Southern roots lead to career in urban forestry

WHILE PERCHED atop a tractor, with his father by his side, Joshua Simon became a lover of the land beneath him.

Planting pecan trees on his family’s farm in Morganza, La., was one of the things he enjoyed doing the most when he was a pre-teen. Not only did the trees provide nuts for pecan pie, a quintessential Southern staple, but, once grown, they provided much-needed shade from the blazing hot sun.

No one was surprised, therefore, that Simon planned on studying agriculture in college. But when a stranger suggested he focus on trees, and specifically in cities, Simon was intrigued. He decided to pursue a degree in urban forestry at nearby Southern University and A&M College.

While there, he read “Dumping in Dixie” by Dr. Robert Bullard, which chronicles the disproportionate health impact of petrochemical plants on Black Americans in the South. Simon realized that decisions about where to locate everything, from industry to trees, can have long-term ramifications for people’s health.

Trees can improve health by cleaning the air people breathe and reducing stress. But a map of tree cover in cities is too often a map of income and race. Often in cities, trees are sparse in low-income neighborhoods and some neighborhoods of color.

Now a master’s student at Ohio State University, Simon is researching how social and economic class status may influence who has access to green space. As part of his work, he is studying patterns among Black, White and East African immigrant populations in Columbus, Ohio, home to the university. Surveys from three census tracts reveal all populations visit parks but at different rates. People with higher incomes use parks more frequently and often have access to higher quality parks in and outside of their neighborhood.

“There’s little research about the socioeconomic dimensions that affect green space access and use in Columbus,” says Simon. “I want to make sure Black and Brown communities have equitable access to the benefits of trees.”

Simon believes understanding how various populations want to use and access parks can help cities make better decisions about where more trees and parks are needed — whether they’re mighty oaks in a busy city or pecan trees in a tiny town.