By Jared Lloyd

I FEEL LIKE I’M LOST inside of Joseph Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness.” This place is exotic. Hot as hell. And, there are a whole lot of things that can go wrong. Adding to this, the topography has a split personality: pocosin, savanna, repeat. The air is thick, the light low. The shade would come as relief if not for the relentless mosquitoes jockeying for position, thrusting proboscises into our skin for a meal.

Watch out for the boot-sucking mud. The tangle of vines, thorns, the litany of evergreen shrubs species that interlock forming a veritable fortress a mile thick and the occasional cypress knee to test your balance. In 1539, the chroniclers of the De Soto expedition wrote of a trackless wilderness near this place, one that took days to travel just a few miles. Men were bogged down in mud, drowned by the weight of armor and they all nearly starved to death. Survival was as bleak, and the danger as extreme, as any ambush by local tribes. A classic pocosin experience,

if you ask me.

This is the realm of fire, and species here begin to stretch the limits of imagination in their adaptations to this brutal fact. Consider the plants: The harshness of life in the longleaf pine savannas has tweaked and molded many into insect-eating monsters. Several species of pitcher plants, for instance, can be seen with a cursory glance across the landscape — each with their own unique way in which to lure in unsuspecting insects to their sweet-smelling, yet toxic, brew of digestive enzymes. In all, there are 17 different species of carnivorous plants here, including the Venus flytrap, an evolutionary rock star in this savage garden.

In the thick tussocks of wiregrass that so characterizes this habitat, I take note of the shocking array of life. Several different species of orchids can be found blooming across this grassland right now. Spreading pogonia, grass pink and a variety of different Spiranthes give the impression of some sort of grandiose Jackson Pollock painting, with random explosions of vibrant colors splattered with abstract expression over the otherwise monochromatic green hue of the savanna in the spring.

Before me stands a cluster of old pines. These are longleafs, as is everything standing in the savanna. But, this bunch comes with white rings painted around their base by researchers to signify their importance.

The normally reddish hue of one particularly heart-rotted pine is plastered in what must be several hundred pounds of sap. Each of the marked longleafs here have sap oozing down the trunk, glistening and baking in the overhead sun. But, this one stands apart from the rest. Towering above the savanna, the bottom two-thirds of the pine looks as though it was literally dipped in candle wax. This is what I have been searching for. The signs are unmistakable, and there is but one species in this forest that could have created such a spectacle: the red-cockaded woodpecker.

THE LIFEBLOOD OF LONGLEAF

For such a small bird, this guy packs a punch. Dwarfed by the immensity of the old-growth longleaf pines and vastness of the savanna, the red-cockaded woodpecker stands a mere 8 inches tall — about the size of an American robin. But, as Napoleon was determined to show the world, size is never a measure of importance.

When it comes to the red-cockaded woodpecker, it’s tough to overstate this importance. So many species that call these longleaf pine savannas home — which is basically anything and everything that makes its home in a tree cavity — owe their ability to survive to this one little bird. Eastern bluebirds, great crested flycatchers, eastern screech owls, fox squirrels, flying squirrels, tree frogs — the list goes on. In all, we know of more than 27 different vertebrate species that depend upon this one bird.

Back in 1994, Ecologist Clive Jones published a paper entitled “Organisms as Ecosystem Engineers” in the journal Oikos. In this, he posed the argument that some species go beyond the basic tenants of what we like to refer to as “keystone species” in the ways in which they impact their environment. By the very habits that their evolution has sculpted them for, these species literally engineer entire ecosystems by their presence. From beavers to alligators, elephants to prairie dogs, Jones and his co-authors on the paper called these species “ecosystem engineers” and defined this term as any organism that creates, significantly modifies or maintains an ecosystem.

Just about every species of woodpecker falls into the category of ecosystem engineer. In most North American forests, there tends to be several species of these birds all working toward the same end: excavating cavities, raising young in them for a season then abandoning those cavities the following year to carve out a new home for a family.

All this cavity excavation really adds up. Throughout our forests, only 1-in-10 cavities are created naturally. This means that on average, 90 percent of all available nesting cavities are created by the handiwork of woodpeckers. The greater the number of these birds, the more cavities in a forest. The more cavities, the more secondary cavity nesters the forest can support. Diversity begets diversity.

Out here in the longleaf pines, however, things work a bit differently. Though other species of woodpeckers live here, their functional impact on the pine savannas is often negligible.

There are exceptions, of course, with both aspen and cottonwood trees in the West coming to mind, but as a rule of thumb, woodpeckers require dead standing trees to show off their master carpentry skills. They simply are not evolutionarily equipped to deal with the copious amounts of sap that comes with excavating into something like a living pine tree — especially champion sap-producers like the longleaf. Researchers have even found birds that have tried hacking open a nesting cavity, completely entombed in the sap of longleaf pines.

This is where the red-cockaded woodpecker comes in, as they are the only species that has learned to navigate the flow of sap in a longleaf pine. A master of its niche, this woodpecker has even come to exploit this characteristic of the longleaf as a defense mechanism — hence, the sap-plastered trees around me. For the rest of woodpecker world, at least in the Southeastern U.S., they are segregated to dead standing trees — the veritable “other side of the tracks” down here. But, in the longleaf forests, those requisite dead snags they so depend upon are often non-existent.

BAPTIZED IN FIRE

The longleaf pine ecosystem is a world that finds itself routinely baptized in fire. Everything about this place promotes combustibility and needs a good old-fashion inferno to continue its way of life. From the rate and pattern at which the longleaf grows, to the unique way in which the bark of the tree disperses heat by scaling off, it all functions to keep this tree alive and insure the continuation of its species in the face of flames.

Lots of pines are fire-adapted. But, the longleaf is more than just evolutionarily armored against it. It’s as if the entire biochemistry of this species was designed to explode after death. Dead branches littering the ground, dead trees standing or fallen, they are all incendiary devices. Couple this with the ubiquitous wiregrass that itself has evolved a host of fire-promoting traits, and you have a tinder box waiting to blow at any moment.

Why would an entire ecosystem help set fire to itself?

“Botanical arson as a means of incinerating the would-be competition” is how conservation biologist and Cambridge professor Andrew Balmford explains it. “Rather than responding to fire, longleaf has evolved to promote it. . .”

All of this fire equates to very few dead standing trees in the ecosystem. Without those dead snags, the rest of the menagerie of woodpecker species here lose their importance. And, thus, the biological diversity of this place rests largely upon the shoulders of our little sap-adapted red-cockaded woodpecker.

As the idea of ecosystem engineers took hold in academia, the number of species that make the list has grown exponentially. Once defined, we have come to realize that species as diverse as blue whales and whitebark pines meet these qualifications, adding even more imperativeness to their conservation. The loss of whitebark pines, for instance, has a cascading effect upon everything from trout to Clark’s nutcrackers to grizzly bears. If we lose the red-cockaded woodpecker, the same holds true for so much of the biodiversity of the longleaf pine ecosystem.

ARCHITECTS OF EVOLUTION

Woodpeckers aren’t just about diversity in the forest, however. Their impact on the world around them goes way beyond that, as species become dependent upon their existence. Though evolution may largely be a survival strategy in the face of catastrophe, it is also the handiwork of time that shapes, mutates and creates.

Outside of the fire-prone pine savannas and the impenetrable jungle-like pocosins of this coastal plain, we move into the bottomland hardwood swamps. This is a landscape of giants. Where bald-cypress reach toward the heavens with outstretched arms and are dated through core samples back to the Roman Empire. Where the gnarled and twisted tupelo gum swell at the base to diameters of 10 feet or more. Red maple punctuates the understory, joined by the likes of buttonbush and highbrush blueberry. This land-scape is neither land nor water, but some kind of tannin-stained blackwater hybrid of the two.

The tide of sightings of ivory-billed woodpeckers from these remote swamps continues across the South. Known as the “Lord God Bird” by those whose habitats overlapped the habitats these birds once haunted, the name was given for the exclamative reaction that people would have when they saw one of these pterodactyl-sized woodpeckers sail past with a 3-foot wingspan.

Down in Louisiana, the last-known living pair of ivory-billed woodpeckers carved out cavities that measured 5 1/2 inches tall by 4 inches wide. But, that was the 1930s. And, an ivory-billed sighting has yet to be confirmed since. Optimism remains, of course. For as Emily Dickenson once wrote, “Hope is a thing with feathers, that perches in the soul. . .”

We can only speculate today, but everything from barred owls to wood ducks most likely evolved to suit the engineering handy work of the old ivory-billed woodpecker. Today, they are all but gone. But, the pileated woodpecker remains, and seems to have had no qualms about picking up were the ivory-billed left off in the world.

It’s a testament to the importance of woodpeckers in the forested world when we can begin to identify select species of animals that have literally evolved to keep pace with the size of these birds. With wood ducks and barred owls sized for ivory-billed woodpeckers, for instance, and screech owls fitting neatly into red-cockaded holes across the longleaf ecosystem, we quickly realize the significant role these birds play as ecosystem engineers, and, dare I say, the architects of evolution in some cases.

THE INTRICACIES OF CONSERVATION SUCCESS

creating a nesting cavity. Credit: Jared Lloyd.

It’s quite a lot to take in for me sitting here in the wiregrass, leaning back against a fire- blackened pine tree as I watch this family of red-cockaded woodpeckers sail in and out to feed their young. The importance of woodpeckers. Their outsized role in the world. The unsuspecting bigness of something so small. The interconnectedness of an ecosystem, intricately woven together like delicate cotton fibers of a Navajo rug. The impermanence of it all. The fact that if we cut but one of those fibers, everything begins to unravel at our feet. And it is at our feet that it all unravels these days, for we are the ones holding the scissors.

The impact that woodpeckers have on their associated forests is undeniable. Some, like the red-cockaded, engineer ecosystems in powerful ways by functioning as the only species capable of building homes in their forest. Others,

like the pileated, have taken over the roles of now extinct species, chopping open giant cavities in trees and creating a surplus of potential homes for those animals of the forest too large for anything smaller.

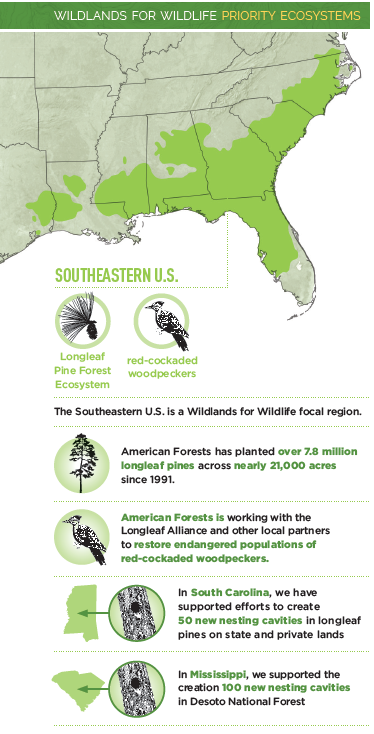

The longleaf ecosystem once encompassed some 90 million acres across the southeast. These trees stretched from Virginia, down along the coastal plain of the southern states, wrapping around much of Florida, and finally coming to an end in eastern Texas. Today, the longleaf pine has been clear-cut down to just 3 percent of its original range, hanging on in a handful of preserves. As conservation groups, such as American Forests, fight to both protect the remaining stands of longleaf pines, and reestablish this ecosystem across the Southeastern U.S., we find that the unsuspecting red-cockaded woodpecker has, in so many ways, become the poster child of longleaf conservation. To simply bring back the longleaf pine is not enough. Conservation success depends upon a healthy population of the red-cockaded woodpecker. For they, like fire, are the lifeblood of this forest.

Jared Lloyd is natural history writer and wildlife photographer. From the coastal rainforests of Alaska to the high Andes of Ecuador, his work takes him all over the world in search of stories and photographs. A native of the islands off the coast of North Carolina, he now lives on the doorstep of Yellowstone in Bozeman, Mont.