On one afternoon in the mid-1930s, Oxford professor John Ronald Reuel Tolkien happened across a mysteriously blank page in one of his students’ exam books, and — moved by who-knows-what, according to the author himself — scrawled down the words “In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.”

Though this was the first sentence to what he would eventually garden into The Hobbit, which led to The Lord of the Rings, that dusty afternoon falls somewhere in the middle of the story. Part of what made Tolkien’s approach so captivating, and so influential, was his belief that no person is separate from — or above — their respective surroundings and histories.

Tolkien was born in South Africa in 1892. He remembered little of South Africa, except for one frightening encounter with a giant hairy spider, as the family moved to England while he was quite young. There, Tolkien moved between the rural hamlet Sarehole, the urban city Birmingham, and King’s Heath.

Photo Credit: Matt Gibson

Sarehole, and the farmer’s mill he remembered most fondly, can be directly understood as the fictional Shire — whereas his family home in King’s Heath hugged busy railroad tracks. Tolkien was orphaned at the age of 12, and in his writings about the Shire we can see him longing for the idyll of Sarehole, gentle parental guidance, and a cooperative community on even terms with each other — such things he unknowingly embraced before life darkly complicated itself.

The young orphan found refuge in Catholicism, as Father Francis from his church looked after him and organized his schooling. He fell in love with a non-Catholic woman named Edith Bratt and eventually was sent to the Somme during World War I. In a trench in France he began the first stories that became the legendarium (the background histories of Middle Earth).

Tolkien, 24 years old at the time of the Somme, served as a communications liaison between officers in the field, using flares, signals, pigeons, runners and telephones to relay messages. On the first night of the assault, 19,240 British soldiers were slain. Nearly 1.5 million lay dead by the end of the offensive. Of his club from school, the “Tea Club, Barrovian Society,” all but Tolkien and one other friend would be killed in action.

How did Tolkien react to all of this? He came to think that industrialization — and machines by proxy — only serves to create different classes of people, with some invariably above, and others by happenstance below. He believed that what inevitably follows this stratification is conflict corresponding to the scale of that divide: Those with the power will use it, and those without will want it.

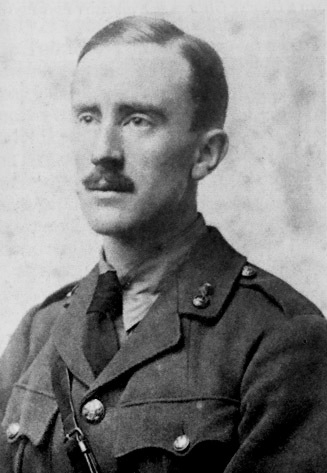

Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

He was sent back to the U.K. to convalesce after contracting trench fever. While healing, he and Edith visited the nearby Roos woods, where she danced for him — a moment he remembered for the rest of his life and immortalized in his legendarium as the tales of Beren and Lúthien, a mortal man and immortal elf who were star-crossed. Thus in nature he found refuge from the wastes of industrialization.

Tolkien’s Catholicism proved significant in his relationship with Edith. Her family originally disapproved of the union, as did Father Francis. Tolkien struggled with supposedly not being good enough for Edith; in this struggle we see Aragorn and Arwen — outcasts in their adopted societies, mired by confusion, death and war, trying to do right by both their country and by their love.

Perhaps most importantly, Tolkien acknowledged that no one is perfect. No mortal, not even Frodo, can totally resist The Ring. Similarly, no human can extinguish the allure of glory, triumph — and celebrity. The struggle between power and grace exists in every heart.

Equally important, however, was the belief that it only takes one person to make a difference. That that person can be anyone, no matter how big or small. That nobody volunteers to do what’s necessary because they want to; they do it because they can’t imagine the alternative.

When you take all of these elements into consideration — the unprecedented mechanical destruction in the form of World War I, causing death at an unbelievable scale; the loss of innocence that comes with being sent from one’s childhood home, and the permanent parting from one’s childhood friends; the finding of refuge in a forbidden lover’s arms, surrounded by the nature whose shelling one has just witnessed; the confusion about what it was all for and what it all meant — when you take all that into consideration, it’s easy to see why the counterculture movements of the 60s and 70s, responsible for the rise of environmentalism, so easily transposed The Lord of the Rings’ fictional representations of these very real biographic events onto what was happening at the time.

Frodo carried the Ring to Mordor. In 1971, a group of activists sailed for the nuclear exclusion zone in Amchitka, with a copy of The Lord of the Rings aboard their boat — The Greenpeace. Thus the international organization was born. They are but one example of the real-world impact of Tolkien on environmentalism, which we examine in Part Two of this blog series.