How people feel the heat of a wildfire’s threat to their homes and livelihoods, and the tale of those trying to fight it.

By Betsy L. Howell; All photography courtesy of the U.S. Forest Service

Four days before I arrived in Republic, Wash., to begin an assignment as a resource advisor on the North Star Fire, the town was ready to evacuate. That Saturday evening, firefighters watched from the U.S. Forest Service Ranger Station as flames began moving down Copper Mountain just south of town. Many of the 1,100 residents had packed their cars and loaded up their pets. They, too, watched from porches and the highest point in town, the cemetery. The evacuation plan called for heading east along State Route 20, up to the Kettle Crest, a long north-south ridge separating the Sanpoil River from the Kettle River. The ultimate call never arrived. At the last minute, bulldozer lines, along with a shift in wind and a drop in temperature, encouraged the flames to settle and even fade out along the fire’s leading edge. Now, it was Wednesday. A gentle, north wind had pushed much of North Star’s smoke south down the Sanpoil River Valley. Upon my arrival in town, I found Republic’s residents going about their business in a hopeful manner. Still, when we spoke, their eyes would turn nervously toward the south.

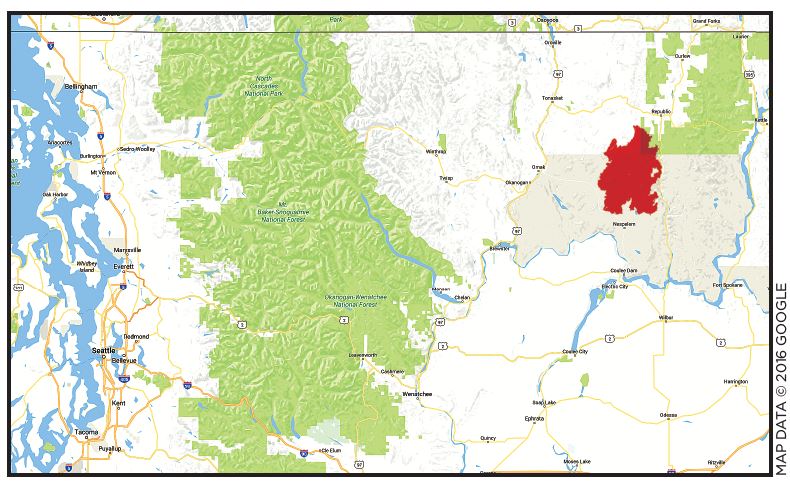

North Star, a massive wildfire that began burning in northeastern Washington State in August 2015, was referred to by newspapers and experts as a “mega-fire.” Ultimately determined to be human-caused, it was estimated at more than 200,000 acres in early-September 2015, a mere two weeks after it began. The bulk of the fire burned on the Colville Indian Reservation south of Republic, while fewer acres, though by no means small amounts, burned portions of the Okanogan-Wenatchee and Colville National Forests.

Traveling to North Star was my second trip to eastern Washington during the 2015 fire season. Where I live on the Olympic Peninsula, adjacent the Pacific Ocean and one of the rainiest places in the world, we had also had a wildfire burning since May. Consequently, even biologists like me, who don’t normally work much on wildland fires, were working them last season. During my first tour on the east side, I had been assigned to two different fires, 300 and 500 acres in size respectively. That was the end of July. The situations were serious, with towns and municipal watersheds, as well as habitat for federally listed species, threatened, yet the sizes of the blazes were manageable, and they responded in predictable ways to fire suppression efforts.

By mid-August, however, everything had changed.

A lightning storm had ignited dozens of fires across Washington and Oregon. Northern California was erupting with fire behavior that didn’t conform to either computer fire models or to the experience of many seasoned firefighters. Descriptions of wild and urban areas being consumed in only hours and fires jumping major highways and large lakes became quotidian reporting. Forests were being lost, and so were people. My first week back at my regular job in Olympic National Forest, three firefighters were killed in eastern Washington. Members of an engine crew, they’d become trapped when the fire suddenly changed direction and triggered a series of catastrophic events.

A week and a half after this tragedy, I once again drove east over the Cascade Mountains to North Star. The nation was now at a Wildfire Preparedness Level 5. This is the highest designation possible and one that reflected the number of major incidents and resources, including people, equipment and aircraft, committed to suppression. Still, there was not enough. Because of a lack of resources, some fires, if not threatening people or homes, were simply monitored and not actively suppressed. Firefighters were arriving from Canada, Australia and New Zealand to help.

Every business in Republic had a sign in the window that read, “Thank You, Firefighters!” This gratitude also resulted in a generous coffee fund available for fire personnel at Java Joy’s right before the turnoff to the Sanpoil River. One woman at Anderson’s Grocery, keying in immediately on my yellow fire shirt and green pants, said gratefully, “Having you people here has really calmed everyone.” Another person on the street thanked me for all I had done. When I explained that this was only my second day in town and that I hadn’t even seen the fire, she smiled. “Doesn’t matter. You’re here now.”

At the Republic Drugstore, I asked the pharmacist for something to help me sleep. I felt glad to be in town and to help however I could, but worry over the second tremendous fire season in a row (2014 had been a record-breaker in Washington State) had kept me awake for several nights. He nodded, looking tired himself, while the cashier thanked me for coming to Republic. She handed me a souvenir key chain.

The last large fire near Republic was the White Mountain Complex of 1988, a sizeable event for the time of approximately 20,000 acres. Bleached snags still stand east of town along highway 20; a green enthusiastic understory grows beneath. Unlike on the Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest to the west where fire is more common, this part of eastern Washington has not had the annual experience of a shutdown tourism industry, closed roads and endless, smoke-filled weeks. Republic, with store facades that call up an earlier time and buildings no higher than two stories, had been stunned by North Star’s vitality. School was delayed and the county fair cancelled altogether. A mural along Main Street conveyed the making of Republic through the growth of the local hydroelectric industry and the taming of the region’s rivers. It seemed clear that this little western town, like so many others, struggled with reminders of how little humans at times can control their environments.

Without question, those most affected by wildfires are the people who have died fighting them and their mourning families, as well as those who have lost their homes or seen their businesses collapse. Yet, the environmental and economic consequences of fires today affect us all. The loss of forests, the degradation of water quality, the destruction of fish and wildlife habitat that we will not see replaced in our lifetimes, are all serious matters. Politically, the situation is also very complicated. Some land managers feel more timber harvest is the answer, while others think fires should just be allowed to burn. Neither of these extreme options are practical or beneficial to the majority of people and wildlife species, so the answer must be found somewhere in the middle. For the five weeks prior to coming to North Star, my mind had been spinning with this predicament and numbers and statistics of wildfires that are difficult to comprehend. In my short 30 years of working around fire, I have seen astonishing changes. For example, in the fall of 1987, I was part of a 20-person crew on the Silver Complex in southwest Oregon. Begun by lightning on August 30 that year, Silver, an event notable at the time for its size and duration, was not declared controlled until November 9. A tally board in fire camp marking the fire’s growth was updated each day and documented Silver’s approach to the 100,000-acre mark. Before my crew left in mid-October, it had achieved this goal. Today, six-figure-acre fires are still noteworthy, but they are not uncommon. “Big” simply does not describe anymore what is happening on the landscape.

Part of my job as a resource advisor is to find ways to minimize impacts from suppression work on valued forest resources, such as fish and wildlife habitat, archaeological sites, campgrounds and trails. This is more easily done when a fire is moving at a pace that offers some possibility of stopping it. When it doesn’t, the emphasis of my work turns to creating a repair plan for afterward. Such a plan may include fixing damaged livestock fences, returning fire lines to more natural appearances, re-closing roads (or reopening them, depending on their status prior to the fire) and restoring stream and wetland systems where equipment and crews have been working. There is a crucial distinction when assessing this workload: that which was caused by the fire itself and that caused by suppression activities. It’s a question of who can be billed, with Mother Nature being notoriously difficult to collect from.

My task one cool, September morning after arriving at North Star involved mapping a bulldozer line off a road that led to Deep Creek, a tributary of the Sanpoil River. The word “Sanpoil” comes from the indigenous Okanagan language and means “gray as far as one can see.” This proved an apt term for the smoky conditions in the valley that day.

I had driven not more than one-tenth of a mile along the road before I encountered a burned tree, fallen and blocking the way. Though there was now little active fire in this area, trees weakened by intense heat around their roots would be coming down for months. Within a few minutes after I requested assistance from an engine crew, Michael Cramer from Chewack Wildfire arrived with two assistants and several chainsaws. Michael, who went by the name of Cosmo, had a bright, smiling face and an enthusiastic handshake. Shortly after cutting out the first tree, we encountered another one down, a 40-inch Ponderosa pine, broken in two across the road and still burning. Yellow and orange flames licked furiously at the tree’s core as Cosmo began cutting out the burning part.

As we moved closer toward Deep Creek, we found more trees down. Most were mature pines and all had snapped at their bases. While the crew cut the trees into pieces, I took photos and made notes. Unlike other parts of North Star, the forest around Deep Creek appeared less a victim of fire and more a cooperator in the dynamic forces shaping wildland ecosystems. Chipmunks and squirrels scurried about, collecting seeds and mushrooms in the unburned portions of ground. Overhead, songbirds and ravens took advantage of insects displaced by the fire and smoke.

When we finally reached Deep Creek, we found a small herd of cattle. A few animals were grazing while others rested along the stream. Cosmo and I looked at them through our binoculars. Some cows had blue ear tags, others green and still others red or white. This rainbow of colors indicated individuals from different herds, and the mixing that had occurred during the fire’s zenith. I felt immensely relieved to see these cows and calves looking healthy and uninjured.

Mackenzie Wilson is from Curlew, Wash., 15 miles north of Republic. At the time of North Star, she was 25 years old, had the sturdy build of a farm girl and had worked as an engine foreman at her previous job. She’d left the eastside to attend Western Washington University in Bellingham, but now had returned to where she grew up and was working as a forestry technician in Colville National Forest. When I met Mackenzie, she did not seem given to unnecessary smiling and maintained a practical, efficient manner. She also was not the least bit sentimental.

Before going to Deep Creek, I had been with Mackenzie in the Scatter Creek watershed, just west of the Sanpoil River. We’d had an engine crew with us that day as well to cut out trees that had fallen across the road. Injured cattle had been reported in the area the day before and we also encountered them, all lying down. While the engine crew filled containers of water for the animals, Mackenzie said matter-of-factly that they would likely have to be put down. One large black and white cow, burned on her stomach and her eyes bloodshot, was in especially bad shape and had not moved since the previous day. Others lay about listlessly. A calf, still mobile, but bleeding and jumpy, would not let anyone get close.

The rancher who owned these animals had been notified, but a more active part of North Star was threatening his home 20 miles to the south. This was the situation I encountered day after day for many residents affected by North Star: homes being threatened or destroyed, livestock scattered and injured, crops and hay lost. Choosing between saving your home and caring for your animals — and, thus, livelihood — seemed an awful decision to have to make.

“Where did you eat last night?” Mackenzie asked me on our last morning together. We were headed to the Cornell Butte Lookout, which had reportedly been burned up by the fire.

“Freckles BBQ,” I said. “They gave us all souvenir magnets and massive portions.”

She shrugged. “It’s a logging and ranching town.”

The fire camp in Republic was what is known as a “spike camp.” The main camp was located in Omak, almost two hours away and on the fire’s western edge. With a megafire like North Star, spike camps are crucial, otherwise crews can be driving half the day just to reach their work areas. Unfortunately, they sometimes don’t have all the amenities; for the moment, the Republic spike camp lacked showers, hand washing stations and an on-site caterer. Though hot food was being transported to the camp in boxes, a number of people had chosen to eat in town.

“It’s good for the businesses,” Mackenzie nodded approvingly when I mentioned the crowds at the restaurants.

A few hours later we found the lookout still standing. The slopes dropping away from it, however, had become blackened moonscapes. The structure had been spared largely because it was mostly metal, but I was still amazed, given the intensity of the fire in this area, that it wasn’t more damaged.

Within the North Star fire area, a lake system west of the Sanpoil River is home to common loons (Gavia immer), a state-listed sensitive species. Swan, Ferry and Long Lakes are three of only 18 sites in Washington where the birds are known to nest. The area is also a popular recreation area, with campgrounds, hiking trails and fishing. Yet, it was eerily deserted, by birds and people, one morning as I scanned the surface of Swan Lake with my binoculars. Informational signs leading to the lake had been encased in protective, aluminum wrap, while an outdoor kitchen, built by Civilian Conservation Corps crews in the 1930s, was being watched over by a sprinkler system. Across the lake, the fire continued burning, though in an undramatic way with more smoke visible than flame. Still, trees crashing to the ground at regular intervals belied the calm.

A big fire like North Star will always have forest stands changed beyond recognition existing beside mosaic patterns of lightly burned and unburned ground. I am never surprised by the strange, unpredictable work of fire, and I also see the many benefits it brings in terms of ecosystem renewal. But, I know, too, that modern human society maintains a decidedly uneasy relationship with one of the main elements of life on the planet. We are living with fire, but we resist tremendously the power it wields. We are very uncomfortable with the uncertainty it creates, and there is no place in the social and economic systems we’ve built for the kinds of far-reaching losses that result from catastrophic mega-fires. As I left the lakes and continued with my day of mapping firelines, I knew I had to focus on my small role in the fire suppression effort, documenting what would be needed after North Star was fully out. If I didn’t and continued to think about the enormous challenges managing fire across landscapes that people and wildlife rely on in many different ways, there would once again be little sleep that night.

The morning I left Republic the temperature sat in the low 30s, and a light frost covered the late-summer grasses. The Sanpoil River Valley was thicker than usual with smoke, the result of controlled burns designed to help keep the uncontrolled areas in check. I met with my replacement, Dave, a Forest Service fisheries biologist from Alaska, who would serve as the next resource advisor with the assistance of Mackenzie. I felt sorry to leave, but also knew North Star would benefit from a fresh set of eyes. On the way out of town, I stopped at Java Joy’s.

“You’re a firefighter, right?” the young woman asked as she handed me my drink.

“Yes,” I said, “but I’ll pay today.”

After departing Republic, I traveled west on highway 20 to the small town of Tonasket before turning south on highway 97 toward Omak. A full two hours of driving 60 miles per hour passed before I finally stopped seeing parts of the North Star Fire.

Betsy L. Howell is a wildlife biologist with the Forest Service currently working in Olympic National Forest in Washington State.