ON A SCORCHING SUMMER DAY in 2017, residents of Richmond, Va., put thermometers on their cars and drove around the city to gather data for a “heat map.”

“We discovered a 16-degree difference between the coolest place and the warmest,” explains Dr. Jeremy Hoffman, a climate change scientist at the Science Museum of Virginia, noting that the extremes clocked in at 87°F and 103°F. The goal: understanding how to direct funding for heat-mitigation measures, drive community engagement on this aspect of equity and improve climate change resiliency.

Dishearteningly, the patterns aligned with census data. Neighborhoods redlined between the 1930s and 1960s, inhabited predominantly by lower-income communities of color, were hotter and tended to have fewer trees and more impervious surfaces. Wealthier, whiter neighborhoods had far more shade and remained cooler.

Photo Credit: Jeremy Hoffman

“That discovery really invigorated our residents and nonprofit partners to see their missions through the lens of environmental justice and equity,” Hoffman says.

As Richmond headed into a second round of heat-mapping, the work began to cross-pollinate with an American Forests’ campaign to gather metrics on 150,000 urban neighborhoods that together house more than 71% of the United States population. The effort helped launch the national Tree Equity Score (TES) in late 2020 and the TES website in mid-2021.

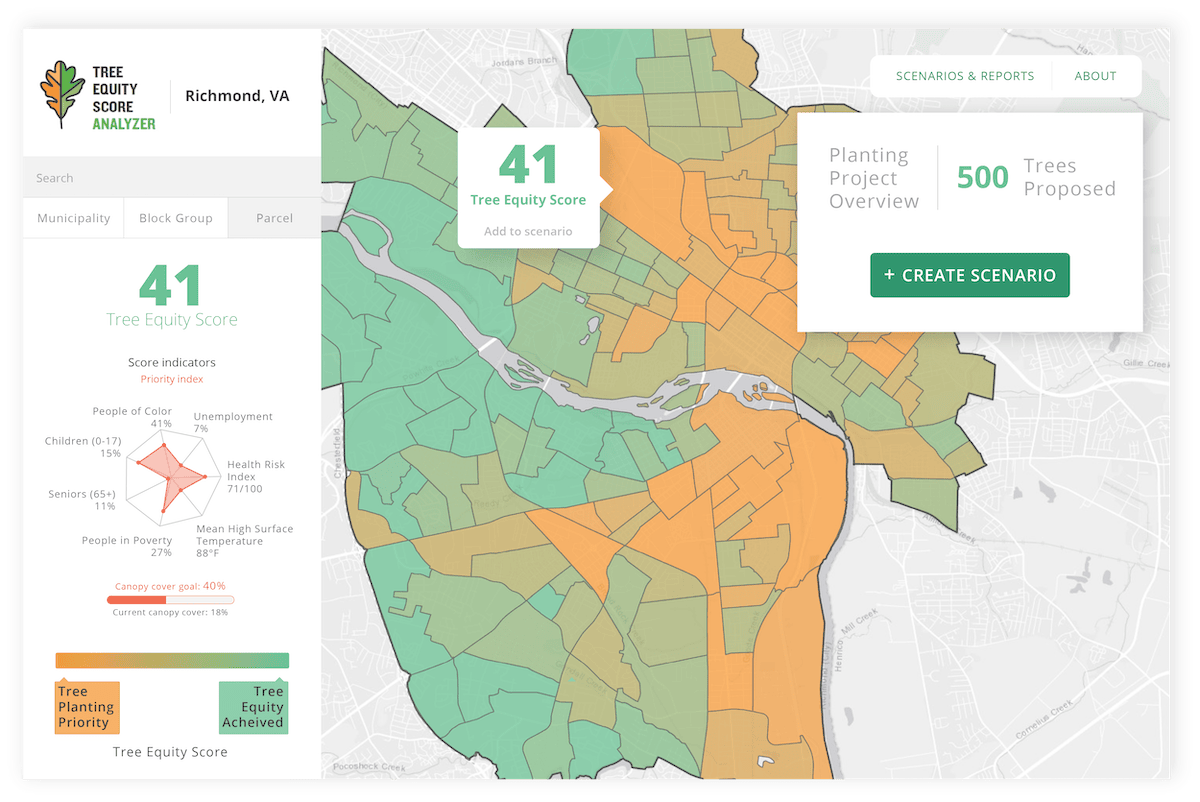

Hoffman became a uniting force among the heat-mappers, community members and American Forests in a joint effort to launch a city-specific Tree Equity Score Analyzer (TESA) for Richmond. The tool, launched in fall 2022, helps frontline organizations, leaders and decisionmakers dive deep into how tree cover coincides with a range of socioeconomic data.

“[TESA] allows you to see the problem as a block-by-block issue, then allows you to solve it block by block,” says Hoffman, who served as a stake-holder council member for the effort.

Photo Credit: Tree Equity Score

The work to develop approaches and tools to address Tree Equity has helped Richmonders attract nearly a million dollars in state and federal funding. This will advance community-driven green space improvements, including efforts to “re-leaf ” the city’s historically marginalized Southside. The support includes a grant from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation to fund the Chesapeake Bay Foundation in planting 650 trees in neighborhoods where residents are 86% Black and Hispanic. It has also helped the Enrichmond Foundation’s TreeLab install 420 trees and 1,540 other plants, some along the budding ProtoPath. This two-mile corridor will eventually connect downtown’s Leigh Street bike lane and the Science Museum. Additionally, its campus is busting up an asphalt car lot and adding those 2 acres to a 6-acre park called “The Green.”

Other benefits are emerging from the heat-mapping and Tree Equity work, like a better sense of how trees aid the stormwater system and could prevent sewer overflow into the James River and Chesapeake Bay. Hoffman says: “It’s a natural outgrowth — pun intended! — that we go from trees as a heat-mitigation strategy to talking about how they soak up rainwater and help turn a gray concrete funnel into a great green filter.”

Tree Equity is a long game, however, as Hoffman points out. “Not only do we have to wait 10, 15 or 20 years for the canopy to mature, but we also have to factor in displacement, migration and gentrification.”

Yet despite these challenges, the effort is essential for ensuring cities are livable for all residents in decades to come. American Forests’ Director of Climate and Health Molly Henry applauds these steps in Richmond and other cities across the U.S. “We have a history of systemic racism that’s reflected in our land use. We have a responsibility to communities that are going to be hit first and worst by climate change.”

And trees can not only help protect communities, they can also contribute to climate solutions, Henry adds. “How amazing is it to have something already here in our world that can do all these things?”

Hoffman’s colleague Jennifer Guild, the Science Museum’s manager of communications and curiosity, agrees that it’s inspiring that well-placed trees can have such profound benefits. “Sometimes people get overwhelmed with the amount they feel they have to do to be an environmentalist,” she says. “We’re showing even small steps can make a big difference.”