The success of the Kirtland’s warbler proves the Endangered Species Act can be exceptionally effective

By Doyle Irvin

IT BEGINS WITH PASSION. This became abundantly clear as I talked with conservationists in Michigan, who are excited about the potential delisting of the Kirtland’s warbler under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). The tiny songbird can be viewed as one of the greatest successes of the ESA — proof that policy really works.

“Everyone is positive,” Jerry Rucker told me when I asked him if there were concerns about the potential delisting, which is still in the works as the details get hammered out. Rucker leads the Kirtland’s Warbler Alliance, a non-governmental organization (NGO) based in the heart of the warbler’s territory.

“The recovery team — comprised of agencies, researchers, university folks and other interested volunteers — has worked for more than 40 years to get here,” Rucker said, “to ensure the viability of the species.”

This detail about the diversity of those involved is especially poignant — frequently the conversations surrounding endangered species omit just how many man-hours and contributions from various backgrounds that conservation work requires. It’s a lot of work, but the reality of its impact is undeniable.

“The bird went from 200-something in 1974 to almost 4,000 today,” Rucker said. “From a social standpoint, I think the future is pretty bright.”

Rucker was counting both males and females — typically the census just marks the singing males — but the numbers quite clearly point to the overwhelming success of the conservation movement since Kirtland’s warblers first became a priority in the 1960s. Already on people’s radars when the landmark ESA became law in 1973, the original recovery goal for the warbler was 1,000 singing males. They passed that goal in 2001, and they have more than doubled since.

HOW DID WE GET HERE?

Due to habitat loss and other factors, the species is now entirely conservation-reliant. This means that they require consistent upkeep and, barring a major reworking of how humans impact the environment, it also means that they will only survive for as long as the passion to sustain them continues. This was not the case 200 years ago — so how did we get here?

“Settlement was attempted in these fire-prone forests, with really dry ground,” Kintigh continued, referring to the jack pine forests that Kirtland’s warblers call home. “A lot of the land was opened up for agriculture, but then much of the land was abandoned because you couldn’t make a living on it. It was too sandy, too droughty and too prone to burns.”

Not all of the land was abandoned, though, and enough people stayed in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula that fire-management policies were put in place to protect human lives and property. These policies interrupted the natural regeneration of warbler habitat and, in tandem with an influx of parasitic cowbirds, caused the decline of the songbird’s population.

Fortunately, the land that was abandoned returned to the state’s land management agencies — the same agencies that led many conservation campaigns. This timeline of events contributed to what you could call a “perfect storm” when it comes to endangered species conservation: You had a calamity on your hands, with a species on the brink of extinction, but you also had the right people in the right place at the right time ready to do exactly what was needed to bring them back. They ended up with a fairly novel solution: integrating private, for-profit companies into the conservation work.

“Endangered species management is so often in conflict with economic interests — just look at the situation in the San Joaquin Valley between agriculture and endangered species,” Kintigh said. “So, it’s unique to have this story where you can provide economic benefits at the same time that you’re saving an endangered species. The two are done in concert.”

THE COMPLICATIONS

The warblers face three major problems caused by human impact, and the folks in Michigan have figured out solutions for two of them so far. The first problem is that warblers only nest in stands of jack pine trees that are less than 20 years old, and they prefer those stands to exceed 80 acres. They are, you could say, particular. This means that the warblers need a constant supply of new, young trees. Normally, that would only happen through wildfire.

“Not understanding the role of fire in our forests is probably one of the biggest blunders natural resources science has made in the last hundred years,” Eric Sprague said.

As vice president of forest restoration at American Forests, Sprague is intimately involved in solving problems faced by struggling forests, but initially it seems backwards — not enough fire? Really?

The truth is that the jack pine ecosystem has adapted to wildfire. The tree’s cones open and release their seeds under high temperatures. Because fire will clear out other trees, the newly released jack pine will have ample space and good soils to regenerate and set the stage for the next jack pine dominated forest. Without fire or management that can mimic it, other trees will establish and discourage the Kirtland’s warbler from nesting.

The problem is that we are not adapted to wildfire. When people live near nesting sites, fires become far too risky, as the tragedy of the 1980 Mack Lake Fire made quite clear. It was thought that bringing back controlled (“prescribed”) fires could help the warbler, but one got out of control. By the end, 25,000 acres had burned, 44 homes were destroyed and a fire technician had perished.

“I hope that warbler enjoys his nest,” Joe Walker reported to American Forests magazine at the time. “My nest is burned.”

Prescribed fires — and natural wildfires — from then on were put out as quickly as possible, even in conservation areas, preventing the natural creation of Kirtland’s habitat in the lands set out for them.

The second problem facing these warblers is nest predation by cowbirds. Cowbirds lay their eggs in songbird nests and sometimes push the other eggs out. Their eggs hatch first and their hatchlings monopolize the food, meaning the other chicks die. Of course, they don’t only target Kirtland’s warblers — they predate on more than 200 other species as well.

“I don’t want to make it seem like cowbirds are the enemy,” Sprague says. “Because they’re not; they’re cool birds. They’re just exploiting our changes to the landscape.”

What he means by this is that cowbirds, who evolved to follow now-non-existent bison herds across the plains, move into land cleared for agriculture in previously forested areas. These new habitats are filled with local songbirds that have yet to develop defense mechanisms. Simply put, the Kirtland’s warbler and its Michigan compatriots don’t know that they need to push cowbird eggs out of their nests.

The third problem that our warblers face is that they winter in The Bahamas — a little out of reach for the Michigan DNR. With climate change, rising seas and increasing hurricane intensity, the health of habitats in The Bahamas is questionable. For some birds, this wouldn’t be a problem: They’d just fly somewhere else. But Kirtland’s warblers exhibit what is called “fidelity,” meaning that they instinctively return to the same spots every year.

PROFITABLE PARTNERS

Integrating private companies into the conservation effort has helped mitigate the first two problems. Four decades ago, warbler enthusiasts figured out that harvesting and replanting jack pine mimics the natural recycling of forest stands that happens with wildfire, and it mimics it closely enough that the ecosystem is able to thrive.

“It’s not a perfect system, by any means,” Kintigh said. “But there are a lot of things about the harvest that do replicate the service provided by wildfire, and we put a lot of effort into paying attention to that.”

He mentioned that many of the other plant species that thrive in jack pine ecosystems (and there are a lot of them) are fire-adapted to changing light conditions — when the canopy burns down, the amount of sunlight changes — and that their harvesting practices provide the same kind of variation. This is the kind of attention to detail that makes the process more than just timber harvesting.

“It’s a very closely monitored process,” Kintigh said. “The private sector goes through a competitive bidding process, then we have administrators who make sure that the harvests are done in an ecologically appropriate, sensitive manner.”

While poor harvesting practices can lead to forest health challenges, carefully managed harvests can be one of our best conservation strategies. The most severe environmental impact from deforestation comes from removing trees and not reintroducing them. By rapidly replanting the managed zones, the areas are constantly either forested or reforesting, and aren’t left fallow. As they grow, they are still removing carbon from the atmosphere, filtering water and providing habitat just like we want trees to do. The big upside is that the timber sale provides the state with enough profit to cover the replanting and some of the cowbird control mechanisms. Dan Kennedy, the endangered species coordinator for the Michigan DNR, spoke with me about the funding for the conservation program.

“The timber industry has been a huge part of this,” he said, “and I think that the collaboration between the state agencies, NGOs and private industries could be modeled across the country for successful endangered species conservation.”

That being said, the potential problem with success — delisting — is that access to federal and state funds for conservation becomes trickier. Prior to this, it was the combination of timber sales and state funds that made it all feasible. And, according to Kintigh, jack pine isn’t the most valuable tree.

“Though it’s a positive margin,” he said, “it’s a really thin margin.”

I asked everyone I spoke to if they were worried about the future of the birds if one of its historic support structures gets taken away. The DNR has signed an agreement to continue to support the conservation of the bird, but is also taking steps to hand over some of the management to an NGO like Rucker’s Kirtland’s Warbler Alliance.

“We know our agencies are committed to the conservation of the warbler,” Rucker said. “But we all know that politics are politics. So, we partner with the timber industry, and we are also creating an independent endowment to rely on in the case of some financial emergency, so you know that the conservation will continue to take place.”

This passion to solve for all exigencies is prompting Kirtland’s enthusiasts to explore new methods. They’re considering upping the proportion of red pine in the stands, as red pine is a much more valuable tree for timber. They’re also looking at changing the way in which they harvest the trees, to better promote natural regeneration and, thus, cut down on replanting costs. Scientists are studying the recent downturn in cowbird populations and advising conservation managers as to whether they can spend less on the costly programs.

Long story short, they’re addressing hurdles that get in the way of protecting this treasured songbird. Delisting might mean funding gets a little more complex, but to them it’s just a mark of success.

“We’ve relied on the structure that the ESA provides for a long time,” Kintigh said, “so on the one hand it makes you a little nervous to walk away from that. But, in the end, the success of this program has been built on the coordination and the passion of the people involved, and I know those things will endure past the delisting of the warbler.”

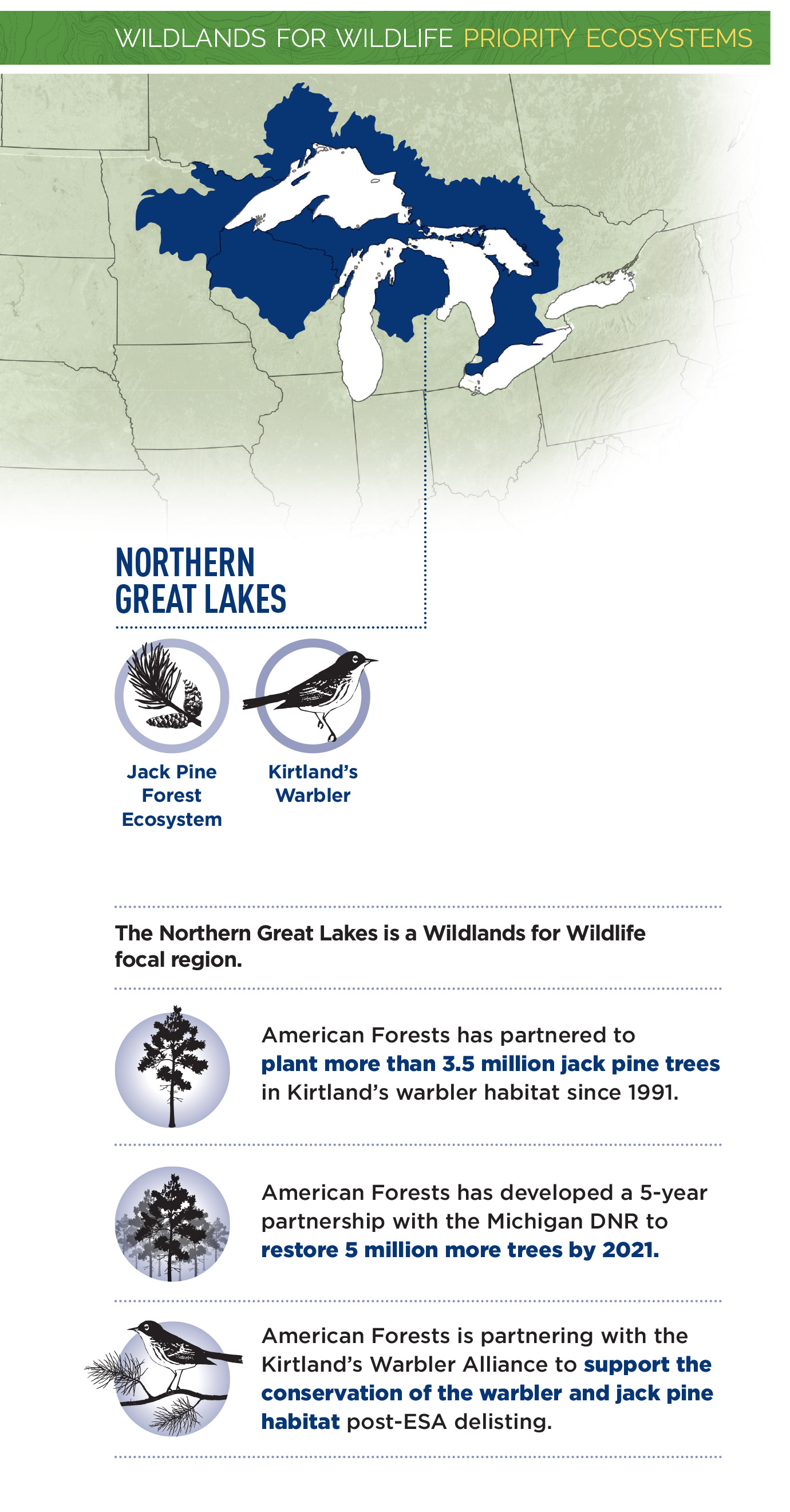

At American Forests, we deeply understand that passion: The Kirtland’s warbler was our very first conservation project in 1990. We’ve contributed to its success by planting more than 3.5 million jack pines and are thrilled with how well the species has bounced back from the brink.

Doyle Irvin is a freelance writer and editor who is passionate about protecting the environment and investing in the future of our planet.