Chuck Graham has circumnavigated the Channel Islands before, but this time, he’s bringing American Forests’ readers along on the journey.

By Chuck Graham

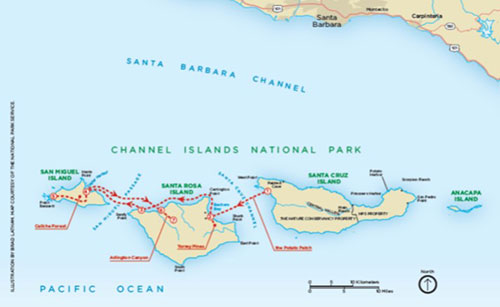

PEERING ACROSS THE SANTA CRUZ CHANNEL, the day was clear enough to see my destination — the grove of Torrey pines overlooking Bechers Bay on Santa Rosa Island, eight miles west of where I stood on a deserted beach on Santa Cruz Island. To get there, I was going to have to kayak across one of the most treacherous channel crossings in the world, where currents from as far away as Alaska and Mexico collide, creating the roiling underwater eddies that force open ocean waves upward. The crossing is known as the Potato Patch, though the potatoes for which it’s named are just one of many cargoes the waves have capsized over the years. Unfortunately, northwest winds were gaining steam and whitecaps swept the Pacific as I set off on my circumnavigation of Channel Islands National Park.

I look at the Channel Islands every day from my home in Carpinteria, Calif., and have been kayaking there for the past 20 years. I’ve made several circumnavigations around the islands, but never tire of exploring this unique archipelago. Each trip is unique. As I stood on the beach on Santa Cruz Island, steeling myself for the Potato Patch, I wondered what this next trip around the volcanic chain, with its diversity of flora and fauna found nowhere else in the world, would have in store.

Known as “the Galapagos Islands of the north,” the chain is best explored from the seat of a kayak. Hidden coves holding freshwater springs, more toothy sea grottos than anywhere else in the world and perfectly groomed golden sand beaches are just a few of the natural wonders found throughout the Channel Islands. Sometimes, it’s difficult to imagine the windswept archipelago is only 90 miles west of the megalopolis of Los Angeles. In fact, paddling the approximately 200 miles of coastlines and channel crossings is like experiencing California before Europeans arrived. During one blustery five-day stretch, I didn’t see or speak to anyone.

Of the eight California Channel Islands, five comprise the national park that was ratified by Congress in 1980. Anacapa, Santa Cruz, Santa Rosa and San Miguel Islands make up the northern chain. The southern chain consists of tiny Santa Barbara Island — the fifth and final island in the national park system — as well as San Nicholas, Santa Catalina and San Clemente Island. My circumnavigation this time would consist of the northern chain and take nine days to complete. I was particularly interested in exploring the islands’ forests.

Of the eight California Channel Islands, five comprise the national park that was ratified by Congress in 1980. Anacapa, Santa Cruz, Santa Rosa and San Miguel Islands make up the northern chain. The southern chain consists of tiny Santa Barbara Island — the fifth and final island in the national park system — as well as San Nicholas, Santa Catalina and San Clemente Island. My circumnavigation this time would consist of the northern chain and take nine days to complete. I was particularly interested in exploring the islands’ forests.

Santa Cruz and Santa Rosa Islands possess the chain’s only forests, some of the most unique in North America, while San Miguel Island’s petrified forest attests to the windswept isle’s distant past as home to a grove of trees.

These forests are important habitat for the archipelago’s wildlife, several species of which, like the bald eagle, have been restored following local extinction or, like the endemic island fox, have been listed as endangered. Santa Cruz Island is the only place in the world to see the island scrub jay foraging for acorns amongst dense groves of island oak trees. Along my pelagic journey, I had many memorable encounters with these creatures and others while kayaking along wave-battered cliffs and teeming reefs and hiking up boulder-choked canyons on this Galapagos of the north.

WHERE EAGLES DARE

From my salt-encrusted kayak, I could hear a majestic bald eagle’s high-pitched whistles carrying down Pelican Canyon on the north shore of Santa Cruz Island. The canyon, shaped like an open book, is shaded by a forest of bishop pines. One tree stood out like no other, though. Its top was flat, browning and shaped like a giant mushroom. An eight-footwide bald eagle nest — successful for the past five years — was once again active with a rambunctious eaglet hopping around the periphery of the nest, its protective parents watching over it.

Santa Cruz Island is the southernmost region for bishop pine forests and important nesting habitat for bald eagles, which were returned to the islands in 2002, following a 50-year local extinction due to DDT pesticides polluting the pelagic food web.

The Montrose Chemical Corp. in Los Angeles was responsible for dumping millions of tons of the pesticides into the ocean along the Southern Californian coast after the substance was banned in 1972. The dump resulted in bald eagles, California brown pelicans and peregrine falcons laying thin-shelled eggs that were crushed before they could hatch. After 25 years of litigation, Montrose was court-ordered to pay $140 million in restitution, with $40 million going toward restoring natural resources like the bald eagle population on the Channel Islands. From 2002 to 2006, Channel Islands National Park partnered with conservation nonprofits to release bald eaglets on the islands. Today, there are approximately 60 bald eagles reestablishing old territories across the islands, successfully breeding, nesting and rearing their chicks without human intervention.

During one memorable encounter, I was paddling along the south shore of Santa Rosa Island in challenging northwest winds. To avoid the biting winds, I paddled inside of Cluster Point, a deep cove that provided shelter from the northwest, ducking out of the winds to eat and drink. There was a colony of northern elephant seals wallowing on a windblown beach. An opportunistic bald eagle approached the periphery of the group looking to scavenge on what it thought to be a marine mammal carcass. Just as it went to taste test a 3,000-pound bull elephant seal, the massive animal reared upward. Wings outstretched, the bewildered raptor was instantly blown away by the whistling winds all the way to the next secluded cove eastward. This natural moment caught by a lone kayaker was one that, just a decade ago, had not been seen for 50 years.

OUT FOXED

After negotiating heaving surf and powerful currents in the Potato Patch, I finished crossing the Santa Cruz Channel to Santa Rosa Island. I landed my kayak below the steep sand dunes at Water Canyon, tucked inside Bechers Bay. After pitching my tent, I went for a hike into the Torrey pine forest. There are only two Torrey pine forests in the world. The other is located in San Diego, Calif. These slow-growing pines require sandy soil in coastal sage scrub communities. Due to the conditions they live in and low genetic diversity, they are rare — the rarest pine in North America. Torrey pine numbers on Santa Rosa Island have been further reduced by cattle grazing. In the early 20th century, there were only about 100 trees in the wild, but through conservation efforts, there are roughly 3,000 Torrey pines today. These amazing pines have broad, open crowns and can grow anywhere from 25 to 50 feet tall. Their cones are heavy and stout but the pine nuts are edible.

I began my hike along an old ranch road, making the steep ascent into the forest from there. About halfway up the grove, I came upon three playful island foxes clambering and jostling on the lowest limbs and chasing each other up and down the thick trunk of a Torrey pine tree.

Native island foxes inhabit three islands in the national park. Santa Cruz, Santa Rosa and San Miguel are the only islands with year-round water sources, and the tiny, 3-to-4-pound island fox is the apex land predator on each of them. However, 14 years ago, the house cat-sized fox was nearly extinct — a casualty of 150 years of ranching across the chain from the early 1830s through the late 1980s. Toward the end of the ranching era, the feral pig population exploded to approximately 5,000 animals on Santa Cruz Island, eventually becoming a reliable food source that lured non-native golden eagles from the California mainland. Unfortunately, the raptors soon learned the island fox was a much easier catch: The smallest Canis in the world had never been preyed upon and could not have anticipated the aerial assault.

Santa Cruz Island is the largest island off the California coast and has historically possessed 1,500 island foxes. Golden eagles eventually colonized the island in the late 1990s and quickly brought that number down to just 50. Populations on Santa Rosa and San Miguel Islands were at critical lows as well, with only 15 individuals on each islet.

In 1999, Channel Islands National Park began captive breeding of island foxes. In 2002, the diurnal island fox was placed on the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Endangered Species List. During captive breeding, the national park began trapping and removing 43 golden eagles, returning them to northeastern California with GPS tags. They also hired a company from New Zealand that specialized in eradicating non-native animals from islands to help with the feral pigs, who were uprooting native groves of island oak and ironwood trees and destroying other island flora.

By 2008, the tide had turned. Golden eagles had been removed and were kept at bay by the return of the bald eagles — who eat fish, not foxes — and by the eradication of the feral pig population. Captive breeding on each island helped to solidify the island fox population. Today, those populations are at or near historical counts, with much of the island flora healing on its own, returning more of a natural balance to the volcanic archipelago.

GHOSTLY TREES

Hunkered down near Sandy Point on the western tip of Santa Rosa Island, I was contemplating when to paddle across the San Miguel Passage to San Miguel Island and continue my journey to its westernmost point. San Miguel, with its natural history, 12 types of seabirds and massive seals and sea lions crowding quiet beaches, is my favorite isle. I scanned the channel with my binoculars, hoping to gauge the difficulty of my crossing. Northwest winds were on the rise, but it was only a three-mile paddle across the passage to San Miguel. I chose to go for it, hoping to reach the inside of scenic Cuyler Harbor before darkness fell.

I reached the island in less than an hour, but the winds increased as I approached the breathtaking cove, and it became an arduous struggle to beach my kayak where the sweeping sand dunes at Cuyler Harbor awaited. From there, I gathered my gear and gratefully trudged up Nidever Canyon to the rustic campground. It felt good to be on my feet, marveling at the native flora like island poppies and buckwheat. A lone island fox sitting atop the picnic table in my site was the only other soul in the campground.

The next morning, I lit out on the trail to Point Bennett located on the northwest tip of the island. Along the way, I stopped at Caliche Forest, a ghostly grove of sand casts made up of calcium carbonate encrusted around ancient tree trunks and roots. The combination of perpetual wind, fog, sand and other particles coming together to create this thick, paper mache-like layer around each gnarled stump gives this petrified forest a ghostly appearance.

Scientists theorize that these trees may have been food for mammoths before they went extinct 10,000 years ago. The Channel Islands were created by volcanic upheaval about 25 million years ago, when a large mass of land broke away from what is today San Diego. At its closest, the resulting super-island scientists have dubbed Santarosae was just five miles from the mainland. Columbian mammoths could smell food on the island and, Pachyderms being good swimmers, could make the channel crossing. There were minimal but sufficient food sources for the 14-foot-tall herbivores. However, when the polar icecaps melted roughly 12,000 years ago and sea levels rose, the chain was formed and the distance to the mainland doubled, stranding the mammoths for good. Due to isolation and increasingly scarce food sources, the mammoths evolved over time into a pygmy species only 4 feet tall at the shoulder. What happened to them next was a question whose answer awaited me back on Santa Rosa Island, near the end of my journey.

THE FIRST ISLANDER

The bow of my kayak eased atop a dense flotsam of tangled kelp and splintered driftwood where cool spring water fed a freshwater estuary at Arlington Canyon on the north shore of Santa Rosa Island. After dragging my kayak above the high tideline, I put on my trail shoes and hiked up the narrow canyon to one of the most important anthropological sites in North America.

Scientists theorize that the pygmy mammoths may have eventually been hunted to extinction by the first humans on the Channel Islands. The oldest human remains in North America were discovered at Arlington Canyon in 1959 by anthropologist and paleontologist Phil Orr. Known as “Arlington Man,” the two femurs found above the creek are 13,200 years old.

As I stood where Orr unearthed his monumental discovery, I understood why Arlington Man chose this spot to live. He had a year-round water source and advantageous view of his surroundings and could live off what the sea provided. Whoever Arlington Man was, he decided to break away from the mainland and venture across the channel in his own makeshift watercraft, possibly constructed from driftwood, willows and deer sinew.

The northwest winds had become a mere whisper and, with them, the swell had vanished too. As I completed the remaining 32 miles across a now-glassy channel back to the mainland where I live in Carpinteria, Calif., I couldn’t imagine paddling something as likely unseaworthy as Arlington Man did so long ago. But Arlington Man may not have been thinking about that when he built his watercraft and made his journey. His thoughts may even have been similar to mine: When looking across the channel at the islands, all I wanted to do was paddle around them. They simply beckoned. I like to think that’s what was going through Arlington Man’s mind as he gathered all the natural materials available to him to build his craft. Called by the islands, he paddled to a unique ecosystem rich in biodiversity — so close to the mainland yet worlds apart — eking out a life on the sea.

Chuck Graham is a freelance writer and photographer based in Carpinteria, Calif., and editor of DEEP Surf magazine. Learn more at www.chuckgrahamphoto.com.