By Tyler Williams

Summer time is camping time. After the erratic weather of spring and before the chill of fall, no time of year beckons our primal bonds like the warmth of a summer evening. And no environment wraps us in close embrace quite like a summer forest, robust and alive during the time of high sun. So get out there: into the woods, up to the high country, down along the creeks and under canopies of pine needles, oak leaves and cedar boughs. Breathe some good air. Get grubby. Melt into the womb of America’s forests. It’s summer.

There are summertime forest haunts across North America, from ocean to ocean and tropics to tundra. Picking just a few camping locales is no easy task. The places featured here showcase a variety of forest environments — from the famous to the forgotten, with a focus on the unusual. Should you undertake a camping mission to one of these places, a pleasant surprise is likely in store because no amount of reading can prepare you for the smells and sounds and sights of actually being there.

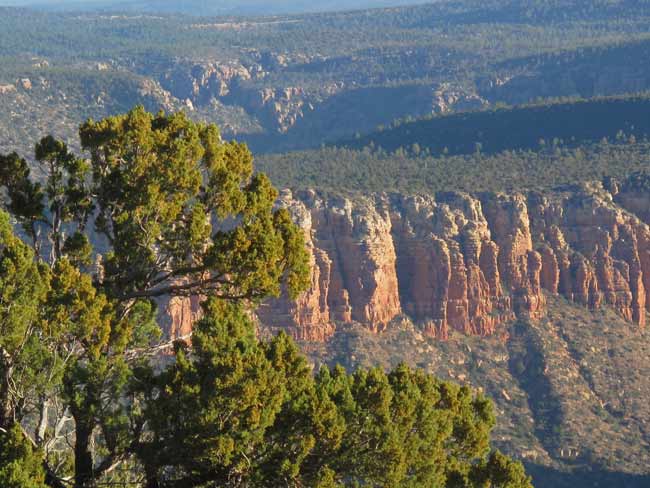

MOGOLLON RIM

One might not think of Arizona as a place to camp in a forest. This is the land of cactus crags and red-rock vistas, right? True enough, but sandwiched between the scorching Sonoran Desert in the south and the vast, wind-swept plateaus in the north lies the Mogollon (pronounced Mogey-own) Rim — a 7,000-foot-high island of forest.

The Rim forms the southern margin of the Colorado Plateau — that desert province of surreal beauty that is home to Grand Canyon, Arches and a half-dozen other non-forest-oriented parks. The southern prow of the Colorado Plateau, however, efficiently captures approaching moisture, and annual precipitation on the Rim exceeds 30 inches, downright damp for the arid Southwest.

The result is the largest contiguous ponderosa pine forest in the world. This is a stately, open woodland, where the underbrush is so minimal that one can stroll anywhere among the pines — trail or no trail. Dive into one of the Rim’s shady canyons and the story changes, with dense pockets of white and Douglas fir, prickly New Mexico locust, quaking aspen and delicate bigtooth maple.

Backpacking opportunities exist in these quiet draws (check out East Clear Creek for cool forest splendor or the Highline Trail for Rim majesty), while developed campgrounds perch in the flat forests above. There are many miles of backroads in “Rim Country,” as the locals call it, where one can pull aside onto a cushion of pine needles and call it camp. If you need a water fix in this humidity-starved highland, man-made lakes dot the forests of the Rim.

When to go:

June is achingly dry, often with campfire bans in effect.

July ushers in needed summer showers from the south.

August typically has clear mornings with thunderstorms by afternoon.

More Information:

Apache and Sitgreaves National Forest:

www.fs.usda.gov/asnf

LAND OF CANAAN

If the mugginess of summer has you longing for Canada, but the burden of such a journey is just too much, take solace: Canaan is near. Deep within the rural fortress of Appalachia exists a little slice of the north, a place where spruce trees line tundra-scapes and a chill breeze blows, even in July.

West Virginia’s Canaan (pronounced Kah-nane) Valley and Dolly Sods Wilderness sit astride the eastern continental divide, occupying a northland niche on the roof of Appalachia. The Canaan Valley floor is more than 3,000 feet in elevation. The “Sods,” as the locals call their mountaintop meadows, are 1,000 feet higher still. In three directions, this is the highest rise of land for hundreds of miles, hauling down more than 150 inches of snow annually (250 inches in 2010) and furthering a red spruce forest of epic stature.

The lure of this rich forest actually cursed the area a century ago, as voracious logging denuded the mountains surrounding Canaan. The leftover humus layer of soil burned to bedrock in many places, prompting the Civilian Conservation Corps to conduct an ambitious topsoil replacement project in the ’30s, along with reforestation efforts. Today, the old-growth might be gone, but the area has recovered well. Burgeoning forests of balsam fir, hemlock and 80-year-old spruce thickets remain. Big Bend and Red Creek Campgrounds will place you close to the forest depths.

Perhaps the most intriguing habitat in the area, however, is where the trees don’t grow. Dolly Sods is an open stretch of heath barrens that hold Pleistocene plant remnants and a decidedly Alaskan feel. It’s hardly a stretch of the imagination to walk, in a single day, from arctic tundra to Quebec-esque spruce swamps to Appalachian hardwood forest. The largest tree ever recorded in West Virginia grew near here, a white oak that was 10 feet in diameter at 30 feet off the ground! Behemoths like this are a thing of the past, but excellent stands of black cherry thrive near Canaan these days. You can’t get that in Alaska.

When to go:

June catch the Canaan Valley birding and nature festival early in the month.

August come to see the Eriophorum bloom (a.k.a. cotton grass).

September brings the start of hardwood color.

In October, autumn is on its way out in these far-north boreal bogs of West Virginia.

More Information

Monongahela National Forest:

www.fs.usda.gov/mnf

Canaan Valley National Wildlife Refuge:

www.fws.gov/canaanvalley

NORTHERN IDAHO

Most forest campers are familiar with the woods of the Pacific Northwest because of the region’s towering conifers and rich alpine meadows. Once east of the Cascade Range, however, the fecundity is supplanted by aridity, and the great forests of the coast are thoroughly absent. In Idaho’s Clearwater and Bitterroot Mountains, the transition reverses itself, back to Northwest lush. This far east, Pacific storms have recharged enough to bathe Northern Idaho with steady rains, nourishing a dense cloak of forest that covers a miasma of steep mountains.

This is interior montane forest, once home to legendary stands of Pinus monticola, western white pine. An Asian blister rust introduced to North America in the early 1900s decimated much of the highly valued white pine forest, but decades of silviculture science developed a rust-resistant strain of monticola. Now, white pines sprinkle a forest they once dominated, while luxuriant grand firs occupy much of the pine’s former habitat.

Western larch, ponderosa pine and Douglas-fir thrive here too, but the signature tree of the region is western redcedar. Their lime-green canopies flow in sinuous patterns across the hills, and their fresh scent permeates the atmosphere. In swampy bottoms, redcedar trunks expand to mammoth proportions. The Hobo Cedar Grove near Clarkia, Idaho, holds some of the most impressive specimens. The roadside Devoto Grove along Highway 12 is one of the most accessible.

The Devoto ancient cedars line the banks of the Lochsa (Lock-saw) River, a whitewater gem that runs cold and high in springtime, slower but still challenging in July and usually too low for raft trips by August. Between rapids, the river settles into pools that reflect green from the surrounding forest. There is plenty of riverside camping along the lovely Lochsa, but if scenic route 12 is too busy for you, the wild Selway River flows clear and green just over the next ridge. A dirt road runs along the Selway’s lower reaches. Above that, there is nothing but perfectly rugged trails penetrating the largest roadless tract in the lower 48 states. When you stumble out of the wilds, a hot jacuzzi beckons at Three Rivers Campground, located at the confluence of the rivers. Sit back and gaze at the cedars, firs and pines because despite being removed from the coast by a major mountain range and one desert, you are definitely in the Northwest.

When to go:

June Soaking spring rains can linger here.

July is prime time.

August and September are glorious,

except when forest fires drop palls of smoke into the river canyons.

More Information:

Clearwater National Forest:

www.fs.fed.us/r1/clearwater

Nez Perce National Forest:

www.fs.usda.gov/nezperce

Three Rivers Campground:

www.threeriversresort.com

JOYCE KILMER-SLICKROCK WILDERNESS

The Southern Appalachians are an assemblage of hazy, blue mountains, where rich forests recycle a moist subtropical atmosphere. Clouds hang lazily over rhododendron valleys, prompting mountain range monikers of “Smoky” and “Unicoi” — a derivation of white in the native Cherokee language. Beneath the mists, robust trees flourish.

Logging was slow to gain a foothold in these rugged backwoods. Still, by the early 1900s, most of the big trees were harvested — but not all, as the momentum of industry crossed itself in the heavily timbered Slickrock Creek basin in 1922. That year, a downstream dam flooded railroad tracks that accessed the valley, effectively cutting off the forest from the long arm of the saw. A decade later, the U.S. Forest Service purchased ripe bottomlands along the creek valleys, protecting the spectacular groves. Today, a full third of the Slickrock Creek watershed remains intact across North Carolina and eastern Tennessee, home to arguably the finest old growth in the Southeast. The sheltered, mid-elevation valleys here are known as cove forests, where predominately deciduous species thrive. White oak, red oak, basswood and yellow poplar create a forest of rare grandeur.

Many of the finest specimens can be found along the Joyce Kilmer Memorial Forest Trail, a two-mile, figure-eight loop offering a glimpse into the pre-European Appalachian forest. If the humid cove groves feel suffocating, you might take a drive to nearby Stratton Bald. From the 5,300-foot summit, one can gaze across a sea of forest furtively peeking through curtains of cloud. More than 60 miles of trail wend through Joyce Kilmer-Slickrock Wilderness below, a backpacking haven. If car camping is your thing, Horse Cove Campground is located near the incomparable Joyce Kilmer Memorial Forest grove. Quiet nooks lurk everywhere. Pack your bags because the Southeast holds plenty of misty mountains.

June through August Classic Southeast balminess reigns.

September cools slightly.

October starts the color season.

More Information:

Joyce Kilmer Memorial Forest:

joycekilmerslickrock.org

Cherokee National Forest:

www.fs.usda.gov/cherokee

CALIFORNIA’S NORTH COAST

To most, Northern California means greater San Francisco or maybe wine country. But continue north on Highway 101, a full six hours from the Golden Gate, and you’re still in Northern California. Yet, this place is very much its own. This is the North Coast, home to the world’s tallest trees, spectacular coastlines and a touch of the unexpected.

Just miles away from the dank redwood rainforests of Jedediah Smith State Park, mountainsides open into rocky scrublands of stunted pine. The dramatic change occurs due to nutrient-depleted serpentine soils, which play host to several rare plant species, most notably Darlingtonia californica, or pitcher plant. The sparse slopes contrast sharply against dense thickets of fir, madrone and oak, mingling to form some of the most diverse forests in North America.

This botanical splendor rises above the Smith River, a crystalline jewel that forms the centerpiece of Smith River National Recreation Area. This public land tract offers plentiful camping options. Stroll the ocean beach. Car camp on an open ridge. Fish the Smith. Stare into the canopy of stupefyingly huge redwoods. Scramble to a remote swimming hole. Now, this is summer camping.

When to go:

July through September

Summer brings regular fog to the coast and lower river valleys, adding an ethereal element to hikes in the big trees. If the cool of the clouds gets you down, head inland and upwards. Hot sunshine awaits. Although the area receives more than 60 inches of rainfall annually, very little falls from July through September.

More Information:

Redwood National Park:

www.nps.gov/redw/index.htm

Smith River National Recreation Area:

www.fs.usda.gov/main/srnf/home

Smith River Alliance:

www.smithriveralliance.org

LEAVE NO TRACE

Camping is a chance to get off the concrete, feel the mud between your toes and un-civilize for a spell. Embrace that. When I enter forests, I feel like a guest of that environment, honored with the opportunity to visit wild nature. With this perspective, it’s easy to move lightly on the land and respect all of its elements. The guidelines of Leave No Trace — principles directing outdoor enthusiasts to minimize the impact their activities leave on natural spaces — become less a set of rules and more a way of life: existing simply, purely and naturally and leaving no trace. This attitude is more essential than any list. Still, here are a few tips for camping minimally, without leaving your mark.

Disperse

If an area is pristine when you arrive, spreading your camping footprint will help maintain that quality. For instance, walk away from camp to spit out toothpaste, preferably in an organically rich place. If you have biodegradable items like coffee grounds to discard, go into the forest and sling them in a wide swath. A thousand little grounds absorb faster than a single mound.

Be natural

Walk at least 200 feet from water (and camp) to defecate. If in doubt, walk farther. Dig a hole about six inches deep and bury feces. If the ground is too hard to dig an adequate hole, find a rock or log that you can lift, and replace it afterward. Pack toilet paper in a zip-able bag, or use a natural substitute — a smooth stick (not poison ivy or poison oak!) does the job just as well. You’ll survive, I promise.

Fire Down

During the long days and warm nights of summer, campfires are unnecessary. However, it’s hard to make s’mores without one. So if you have a campfire, construct it in an existing fire ring. If none exists, make a small clearing (a ring of rocks is not needed) for your small fire. Before leaving, douse the ashes until cold, throw any unburned sticks into the woods and re-cover the clearing as if you were never there.

For more information on the Leave No Trace movement, please visit www.lnt.org.

Big-tree-hunter and adventure-seeker Tyler Williams writes from Flagstaff, Arizona, and can be reached on his website at www.funhogpress.com.