The Creation of Acadia National Park

By Michelle Johnson

Just off the coast of Maine sits a large, rugged, rocky island that has been home to various groups of people for thousands of years. In 1604, French explorer Samuel de Champlain noted the large, knob-like peaks that occupied the otherwise barren landscape and gave the island the name Mount Desert, which it’s still known by today.

It wasn’t until the mid-1800s, however, that Mount Desert’s popularity began to rise as artists flocked to the island hoping to capture its pristine landscapes on canvas. Mount Desert quickly became a hot spot for painters and writers. With its rise in popularity, dozens of hotels were established to accommodate the influx of visitors, and tourism soon became a thriving industry in the area. Not long after, wealthy Easterners fell in love with artists’ renditions of the picturesque island, and they, too, quickly made Mount Desert a favorite summer escape. However, the humble lodgings just weren’t suitable to this new breed of visitors, so prime plots of land were purchased by well-to-do families to build extravagant summer “cottages,” as they were called. The construction of these lavish homes began to worry local residents Charles Eliot and George B. Dorr.

Working under Frederick Law Olmsted as a landscape architect, Eliot was inspired to protect natural landscapes, and soon developed his own ideas about how to conserve his favorite vacation spot. Unfortunately, before he was able to put his plans into motion, Eliot contracted meningitis and died suddenly at age 38.

While sorting through his son’s possessions, Eliot’s father, Charles W. Eliot, came across the younger Eliot’s plans for preserving Mount Desert. Determined to see his son’s dreams carried out, he established the Hancock County Trustees of Public Reservations, a nonprofit group of private citizens committed to preserving historic and scenic lands by buying and managing those areas for future public use.

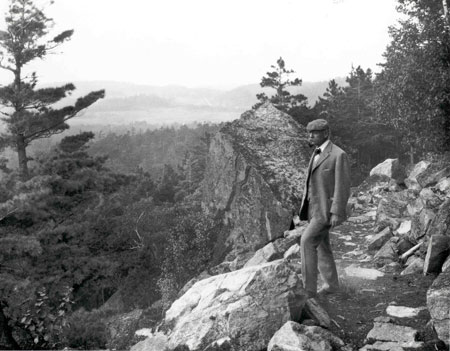

Like the younger Eliot, George Dorr came from a wealthy Boston family that vacationed at Mount Desert. As a young man, Dorr decided to make the island his primary home. He was committed to preserving the natural beauty of his island home, and as a member of the Hancock County Trustees, he spent his days buying up property around Mount Desert and persuading others to donate their land for protection under Maine’s state legislature. Eventually, the trustees acquired a large part of the island, but Dorr soon learned that the state legislature wanted to revoke the trustees’ nonprofit status, which would mean that the land they had acquired would no longer be protected. Dorr quickly set out to bypass the state and appealed to the federal government for greater protection for Mount Desert.

In Washington, D.C., Dorr learned that his herculean efforts were the first of their kind. Never before had a private citizen sought to protect privately donated lands under the status of a national park. After a two-year battle that required him to make frequent visits to Washington to plead his case for the establishment of a national park at Mount Desert, Dorr opted to have the lands established as a national monument, which needed only presidential approval. Though Dorr would have preferred national park status for his beloved land, national monument status would at least offer greater protection while Dorr waited to receive national park status through congressional approval. In 1916, President Woodrow Wilson signed into existence Sieur de Monts National Monument on Mount Desert.

Later that same year, President Wilson signed a bill officially establishing the National Park Service to serve as the agency “to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and wildlife therein, and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such a manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.” Dorr made certain that Sieur de Monts was in line to receive protection as a national park under the control of this new agency. His goal for the land was finally achieved in 1919, when Sieur de Monts National Monument officially became Lafayette National Park, the first national park east of the Mississippi River.

But Dorr did not stop there. He was soon introduced to John D. Rockefeller Jr., who also owned an estate on Mount Desert, and the two put into motion Rockefeller’s plans for an intricate carriage road system throughout the island. Rockefeller envisioned a system of motor-free byways, following the natural contours of the terrain, to travel into the heart of the island, which would take advantage of breathtaking vistas while sparing trees from destruction and preserving the line of hillsides.

The project would be a huge undertaking, so Dorr enlisted the help of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) — a group created by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt as part of his “New Deal” to overcome the hardships endured during the Great Depression. The CCC was comprised of out-of-work men who were looking for a way to not only financially support their families, but also find meaning and purpose in their lives. The group became known as the “Tree Army,” working in forests, parks and rangelands across the country on projects that benefitted the land.

To complete the impressive 57-mile-long project on Mount Desert, Rockefeller himself began buying up additional land on the island to donate to the cause. Each path along the carriage-road system was constructed using quarried island granite for road materials and native vegetation for landscaping, all of which made the roadways able to endure Maine’s often harsh weather and blend into the natural scenery, while keeping the area free of the pollution associated with motor-powered vehicles. Today, this network of roadways stands as an exceptional example of broken-stone roads and is still the best way to take in the views around the island.

Dorr’s dedication to preserving Mount Desert was so great that nearly every dime he had was spent on maintaining and protecting this land. He went on to serve as the first superintendent of the national park, a title he held for 25 years.

Today, the tremendous efforts of Eliot, Dorr, Rockefeller, the CCC and all those who worked tirelessly along with them haven’t gone unappreciated. The park — renamed Acadia National Park in 1929 after the Greek “arcadia” meaning “simple pleasure” — attracts more than two million visitors each year, offers recreational opportunities including hiking, kayaking and wildlife viewing and is open year-round. To plan your trip or to learn more about the park, visit www.nps.gov/acadia.

Michelle Johnson writes from Ft. Lauderdale, Florida, and can be reached at mmjohn82@gmail.com.