By Ruth Wilson

Through the ages and in all corners of the globe, people have looked to trees to make sense of our lives, honoring their transcendental qualities in a variety of ways. How has our interconnectedness with trees manifested itself? The answers are many, but these pages present just a few examples — culled from my own experience and that of others, including the research of Dr. Nalini Nadkarni, discussed in her book “Between Earth and Sky: Our Intimate Connections to Trees” — of how trees meet our needs at every level of human experience.

TREES AND OUR PHYSICAL SELVES

Our strong connections with trees may be based, in part, on the fact that trees and humans share similar physical characteristics. We stand upright, have a crown on top and mobile limbs stemming from a central trunk. The pattern of the tubular branches (bronchi) in our lungs is similar to the root system of many trees.

At the physical level, trees provide oxygen, food and other material necessities, such as paper and building materials.

Trees also provide physical security in the form of shelter, windbreaks and a sense of place — of rootedness. Humans have a strong preference for landscapes with trees or wooded areas. In the real estate market, we find that trees increase the property value of homes by four to 15 percent. In areas where 30 percent or more of the land is federally protected, employment growth over the last 40 years has been three times higher than average, and commercial areas with trees tend to attract more customers, who shop longer and spend up to 12 percent more.

Trees play a role in the context of play and recreation, as well. We use trees for crafting musical instruments and constructing boats and canoes. We have picnics under the trees and take walks through the woods. Eight of the 25 most popular tourist destinations in the United States are on National Park Service land.

TREES AND OUR SPIRITUAL SELVES

At the spiritual level, trees help us become more aware of our connections with something larger than ourselves. In mythology, trees are sometimes portrayed as the abodes of nature spirits. We even have a special word — dendrolatry — in reference to the way we worship trees. Dr. Nadkarni suggests that trees call us to a state of “mindfulness,” where we become better in tune with and more compassionate toward our surroundings.

Perhaps this is why sacred groves have been an important part of various cultures throughout the world. Examples include cedar groves in Lebanon, redwood groves along the Pacific coast of North America, the Shaman forests in south Peru and the Garden of Gethsemane in Israel. In Japan, a large number of Shinto and Buddhist groves are cherished as sacred natural sites, while people in other parts of the world and with different religions have established specific wooded areas as monastic groves.

Early Greeks, Persians and other ancient peoples throughout the globe used the world tree motif — with its roots wrapped around the Earth and its branches in the heavens — to symbolize the potential ascent of humans from the realm of matter to the higher reaches of the spirit or the possibility of mystic access from one plane of being to another.

We also look to trees for healing — not only in the medicinal sense, but for spiritual healing, comfort and solace. We thus find trees in therapeutic gardens and cemeteries and understand why some individuals request having their ashes buried at the foot of a tree or scattered in a beloved forest.

TREES AND OUR ARTISTIC SELVES

Forests and trees have inspired works of literature, art and architecture.

In literature, Thoreau writes about the “living spirit of the tree” and declares a tree to be “full of poetry.” Poet Joyce Kilmer says that he’ll “never see a poem lovely as a tree.”

In art, the tree of life is a common motif used in various forms to represent harmony, unity and connections between heaven and Earth, the past and present, death and rebirth. The symbol takes various forms, but basic elements include roots, trunk, branches and leaves, blossoms or fruit. In the Jewish and Christian traditions, the tree of life is often used to represent the cycle of life, death and rebirth. The Mexican tree of life often depicts religious stories, such as the tale of Adam and Eve or the story of Noah’s ark. The motif is also a traditional Celtic symbol, where it is often depicted as one big circle connecting all forms of life. We use the same tree of life design in “family trees” to depict connections within a family group.

In architecture, we find various components of buildings inspired by trees. Some columns, for example, clearly represent tree trunks; others incorporate different parts of the tree. The palmiform column depicts eight palm fronds tied to a central pole. The palmette — often found in the design of a frieze or border — represents the fan-shaped leaves of a palm tree. Famous American architect Frank Lloyd Wright used the tree of life design in one of his most popular art-glass panels in the 1904 Darwin Martin House.

TREES AND OUR CEREMONIES

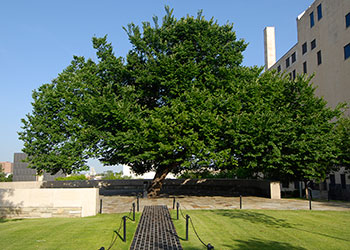

Trees are sometimes planted to commemorate special events, such as the birth of a baby, a graduation or a Bar/Bat Mitzvah. In some instances, trees are used as monuments, such as the Survivor Tree at the Oklahoma City National Memorial, to serve as a witness to tragedy and a symbol of strength.

A tree might also be planted in memory of a loved one who has died. Some people may plant these memorial trees in their backyards or in a cemetery plot, while others may have them planted in forests as a way to honor the deceased’s love for the outdoors. Many people have trees planted through American Forests’ Gift of Trees in Memory program as a way to honor their loved one’s memory.

In other instances, people choose to be buried under trees or have their ashes put into biodegradable urns from which a tree will grow.

TREES AND OUR ENVIRONMENTAL ADVOCACY

At times, deep, personal experiences with trees inspire environmental advocacy. Take Julia Butterfly Hill, for example. Beginning in 1997, Julia spent two years living in the branches of a 1,000-year-old redwood to draw attention to the clear-cutting of old-growth forests. Her actions not only led to an agreement with the Pacific Lumber Co. to preserve what came to be known as “Julia’s tree” and other trees within 200 feet of it, but also to awareness of the need to preserve forests, leading to public support for sustainable forestry research. Yet, for all the impact her vigil in the tree and her advocacy had, they were entirely unplanned. Julia was traveling through northern California when an impromptu stop and a short walk in the redwood forest changed her life forever. It was the spirit of the forest, she said, that gripped her and called her to do what she could to protect the majestic cathedral of the woods.

Author, conservationist and former vice president of American Forests Aldo Leopold (1887-1948) was also inspired by the forest and dedicated himself to nature preservation — not just for the physical well-being of humans, but to maintain the integrity of nature itself. Leopold worked as a forester during a time when forest management was based on a utilitarian view, defined by what is useful for humans. He proposed a dramatic change in how we view and relate to the natural world, advocating a “land ethic” based on preserving the integrity, stability and beauty of the biotic community. His 1925 American Forests’ magazine article, “The Last Stand of the Wilderness,” became the basis for American Forests’ national campaign for wilderness preservation.

TREES AND OUR SENSE OF PLACE

My own experience — which I am sure is shared by many others — also suggests that trees can foster a sense of place. I moved frequently to different parts of the country and found that I could always depend on trees to help me connect with the place where I lived.

I grew up in Ohio, where maple trees framed my life and helped me learn about seasons and cycles and the way things work. I soon learned to anticipate the buds and emerging leaves in spring, shade in summer, brightly colored leaves in fall and the quiet dormancy of winter. In Florida, I found the scent and taste of oranges, grapefruit and lemons more reflective of the Sunshine State than miles of sandy beaches. While living in Washington, I found inspiration in the ponderosa pine and sitka spruce of the Olympic rainforest. These giant trees seemed undeterred in their striving to reach the heavens. I now live in New Mexico, where juniper and pinyon pine stand firm, even in sandy ground and through the onslaught of drought and strong winds. Trees, in each of these very different places, helped me understand and adjust to the environment in which I lived.

Unless moved by humans, trees remain rooted in one place throughout their lifetime, preserving their native character. They stand tall, solid and strong, rooted in the earth. They become an integral part of the place where they live, a contributing member of the biotic community. Perhaps there is no better example for us, as humans, to emulate. Listening to the trees, we can learn not only about a particular geographic place, but also about our place in the larger community of life.

Ruth Wilson writes from Cochiti Lake, N.M., and can be reached at wilson.rutha@gmail.com