By Robin A. Edgar

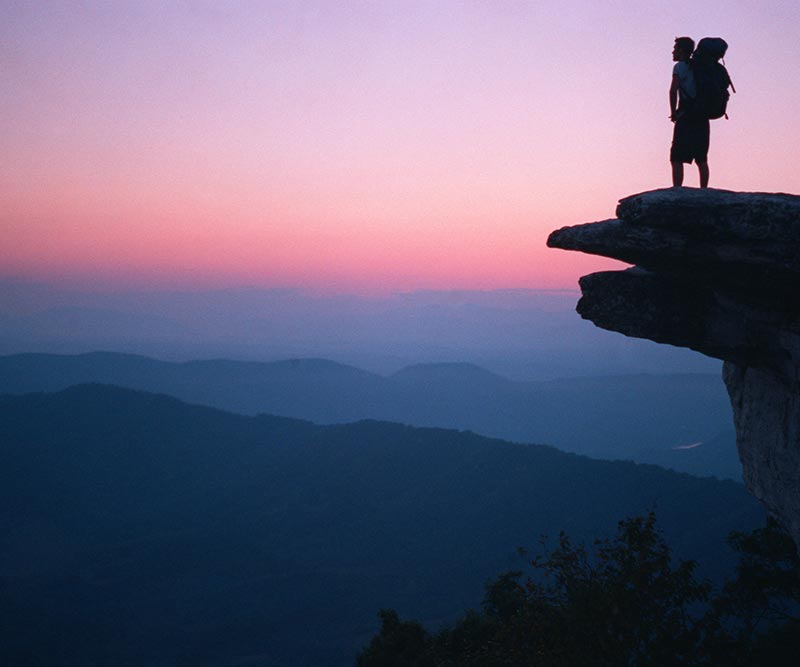

“A footpath for those who seek fellowship with the wilderness.” This inscription, found on plaques at each end of the Appalachian National Scenic Trail, beautifully sums up U.S. Forest Service land-use planner Benton MacKaye’s dream to create what would become the longest continuous, hiking-only footpath in the world.

MacKaye’s essay, “An Appalachian Trail: A Project in Regional Planning,” appeared in the October 1921 issue of Journal of the American Institute of Architects, and work to turn his dream into a reality began quickly, but the trail took more than 15 years to build, requiring the teamwork of a few hundred volunteers working with state and federal agency partners, local trail-maintenance clubs, workers from the Civilian Conservation Corps and the volunteer-based nonprofit Appalachian Trail Conservancy (ATC). The trail opened in 1937, and three decades later, the A.T., as it has affectionately come to be known, was designated as the first national scenic trail by the National Trails System Act.

The lands are still managed and maintained by the ATC today — in cooperation with the U.S. Forest Service, other state and federal agencies and 31 maintenance clubs — and are administered by the National Park Service. The ranks of volunteers have grown since the original few hundred. More than 6,000 volunteers devote more than 200,000 hours of service annually to managing the trail. In the words of the ATC, “The body of the trail is provided by the land it traverses, and its soul is the living stewardship of the volunteers and workers of the Appalachian Trail community.”

The 2,180 mile-long footpath passes through 14 states, from Springer Mountain in Georgia to Katahdin in Maine. Virginia has the most miles of any state — about 550 — while neighboring West Virginia lays claim to just four. Traversing the ridges of the Appalachian Mountains, the trail corridor is 94 percent forested.

Over the years, the trail has undergone a remarkable transformation due to the work of thousands of volunteers. Originally routed straight up and down mountains, trails were highly susceptible to erosion. Trail crews have relocated or rebuilt about 99 percent of the trail in order to maintain and improve the path, making it much more sustainable as well as enjoyable. The trail today is not only better protected, but traverses more scenic landscapes than the original route.

The five million steps needed to walk the entire trail take hikers through six national parks and eight national forests. More than 160,000 white blazes (marks mostly found on the trees along the path) guide them on their way. These hikers must prepare physically and mentally for the hike — from building stamina and breaking in boots by hiking with a full backpack beforehand to buying freeze-dried food and planning menus. Hikers need to be sure to have enough lightweight clothing and a durable tent for any changes in the elements.

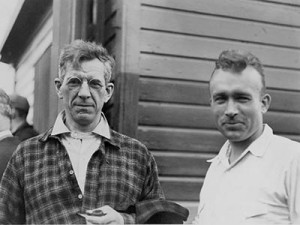

By 1969, only 59 people had completed the trail, including former ATC chair, Myron Avery, who became the first to complete the trail just before its official opening. In 1970, the numbers began to rise with 10 people completing the trail, among them Ed Garvey, who made hiking the A.T. popular with the release of his book, Appalachian Hiker: Adventure of a Lifetime.

The term “2,000-miler” came into use in the late 1970s as more people began to complete the trail. By 1980, the total number of 2,000-milers had increased more than tenfold, and that number would double twice by 2000. Today, the ATC has recorded more than 12,000 completions, but total visitor use is estimated to be between two and four million hikers each year.

Mark Wenger, executive director and CEO of the ATC, says, “It is amazing to see the number of people that have taken on the challenge to hike the entire A.T. The trail offers such wonder and beauty, and it is great to see more and more people enjoy this national treasure.”

GOING ALL THE WAY

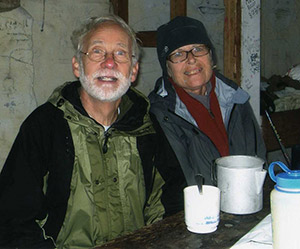

Some 2,000-milers are “thru hikers” — those who complete the entire trail in one year. Thru hikers will typically begin their journey in Georgia in March. Between August and October, about one in four of them will make it all the way to Maine. Mary and Lue Elder are among those few.

The Elders from Young Harris, Ga., started their thru hike on March 1, 2004, and reached the end of the trail on September 15. Flooding from a big storm prevented them from hiking about 40 miles of the footpath in Maine, but they were otherwise well-prepared. They had backpacked quite a bit together and knew how to plan ahead. They made their own dried fruits and vegetables to go with the freeze-dried meals that filled 24 boxes of supplies for friends and family to mail to several towns close to the trail.

Although Mother Nature was not kind to them towards the end, the Georgia couple experienced a good deal of what they call “trail magic” along the way. They encountered local “trail angels” at campsites and shelters, who would cook hamburgers and hearty breakfasts for backpackers who came through. Those angels meant so much to them that the Elders now camp out every year at a clearing on the Georgia portion of the trail known as Cheese Factory Gap to act as angels themselves.

“We cook hotdogs and hamburgers and provide drinks at night, and then cook a big breakfast for the backpackers that camp with us,” Lue Elder says.

Angels like the Elders also played a major role in the adventures of successful thru-hiker Trevor Thomas from Charlotte, N.C. The first blind person to hike the entire trail unassisted, he says angels helped him the entire way.

Thomas, also known by his trail nickname Zero/Zero, used trekking poles to continually scan for obstructions in front of him while also relying on echo-locating to stay on the path. Noting the way sound refracts off rocks and trees allows him to identify his environment. When there is no ambient noise to guide him, he makes a clicking sound with his tongue, which serves a similar purpose to the squeaking sound a bat makes.

Thomas was delighted to find coolers filled with drinks, oranges and apples at trail crossings. He also got rides to town from angels when he needed to re-supply.

“I do not think, without the benefit of the trail magic people, I would have made it from one end to the other,” he says.

ONE MILE AT A TIME

Others hike the trail section by section, spending parts of each summer covering new territory. Though their journeys are shorter, there are still angels to be encountered along the way — and demons.

Over the Halloween weekend in 2011, a freak snowstorm rolled across Chestnut Ridge above Groseclose, Va. Section-hikers Mark and Carol McCall were, at that moment, hiking along the trail overlooking Burke’s Garden, which they had heard was the most beautiful part of that section of the A.T., but “we couldn’t see anything because of the rain and fog,” says Mark McCall. They’d heard about the snowstorm, but thought it was far enough south that it wouldn’t affect them. They pushed on in the rain and kept climbing higher and higher until the wind picked up, and it began to sleet.

As daylight faded, they realized they wouldn’t make it to the nearest shelter, located on the second highest point on the trail south of New Hampshire, and hastily put up a backpacking tent. Soaking wet and too cold to even make a fire, they crawled into their sleeping bags and ate granola bars and nuts for dinner. During the night, ice covered the outside of the tent as the condensation from their breath soaked the outside of their down sleeping bags.

“We survived the night and, packing our soggy sleeping bags, moved on to the shelter for breakfast,” says Carol McCall. As they descended the other side, the day warmed up enough for them to remove their wet mittens and hats.

The McCalls had been well-prepared with warm layers and food that wouldn’t need to be cooked, but lack of preparation can come back to bite even the most experienced hikers.

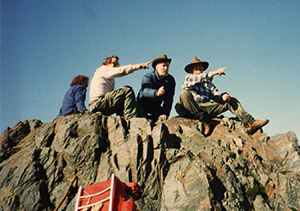

Jeff Carter grew up in Florence, Ala., and has been an avid hiker most of his life. He hiked with friends from medical school before moving to Tryon, N.C., in 1984. “One of the reasons I moved to this area is because it is wonderful for hiking,” he says. He and his wife, Sherry, hiked the Great Smoky Mountains together for a few years before deciding to continue on to do the A.T. in 1988.

Even with their experience, they felt it was good to hike with more people in case someone was injured. They decided to invite others to hike the trail as a group. Although several friends — including, once, the McCalls — have joined the Carters over the years, only two have continued to go with them as a group on hike after hike: Bill Crowell, a local blacksmith in Tryon, N.C. who grew up hiking the backwoods in South Carolina, joined the group in 1988. Jeff Byrd, who grew up camping with the Boy Scouts in Alexandria, Va., started hiking with them in 1990 after moving to Tryon to publish its local newspaper. The Tryon group has hiked about a fourth of the trail together over the years.

Although the trail passes through towns where hikers can restock or use the local post office to receive supplies from home, sometimes lack of preparation takes its toll on the how the journey comes out. Jeff Carter remembers a time when he didn’t plan for enough water for the group’s hike at Angel Rock, Va. It was unbearably hot and there weren’t a lot of springs. They ran out of water, turning their carefree hike in the wilderness into what he describes as a death march.

Safety is not the only advantage to hiking in a group, and it was not the Carters’ only reason for inviting others along. They also gain camaraderie. Sharing the breathtaking beauty of the wilderness along the path brings the group together. Everyone has his or her own favorite vista along the A.T., from the purple rhododendron and orange azaleas lining the woods in spring that Sherry Carter fondly remembers to Crowell’s favorite 360-degree view from Rocky Top, N.C.

Jeff Byrd says, “When someone told me about camping in the Southern Appalachians in North Carolina, I remember thinking that sounded like heaven, so I was thrilled when the Carters invited me to go camping with them.

“The hike up to Spence Field was really a rough reintroduction to backpacking for me, and I was really huffing and puffing,” says Byrd about a strenuous hike in Great Smoky Mountains National Park. “Jeff Carter stood at the bend of each switchback, encouraging me that it was not that much more to go — for the last two hours. I was beginning to disbelieve him,” he recalls, adding that it was worth it once they reached the ridges and camped high up in the Smokies.

PROTECTING THE TRAIL AND FORESTS

Fellow hikers are not the only ones who rely on each other’s kindness on the trail. The natural environment also needs the respect of those who pass through. All hikers, whether there for a few days or the long haul, can have both a positive and negative impact on the woodlands that line the trail. Hikers can ensure that they preserve the natural setting and its creatures by following the “Leave No Trace” principles.

These principles include staying on the trail as much as possible to avoid trampling vegetation, says the ATC’s Laura Belleville. The seeds of invasive species may attach to hiking boots or clothing and can crowd out the native plants that inhabit the area.

Respecting proscriptions against campfires is also an important part of Leave No Trace and can prevent wildfires that can have a devastating effect. In May 2011, an illegal and improperly extinguished fire at the Appalachian Mountain Club’s Ball Brook Campsite in Connecticut demonstrated the importance of Leave No Trace when it spread south along the plateau toward the Riga Shelter half a mile away.

“Conscientious hikers who are aware of the threats to forests can be a very important voice in helping to conserve and manage them,” says Belleville. Well-conserved and managed forests bring A.T. hikers — 2,000-milers and day hikers alike — closer to the “fellowship with the wilderness” that they seek.

Freelance journalist Robin A. Edgar is the author of In My Mother’s Kitchen. She writes from the Carolinas.

For more information:

Appalachian Trail Conservancy www.appalachiantrail.org

Appalachian Mountain Club www.outdoors.org/conservation/trails/at