THE JOURNEY OF WHITE OAK FROM ACORN TO CASK

By Christopher Horn

THE CURVATURE OF A WOOD BARREL JUXTAPOSES THE USUAL FORMS associated with trees and lumber: straight, flat, solid. And while industry creates the barrel itself, nature is the true builder here. The genetic make-up of barrel wood — typically that of a white oak tree — is tailor-made for use as a forest product. From the floors you walk on to the water you drink, the impact of white oak is widely felt — or tasted — and to many, it is the most important tree species in the United States.

The ecological, economic and cultural significance of white oak makes its sustainability an even more pressing issue as the species and the forests it thrives in face tremendous challenges for future viability.

ECOLOGICAL HEAVYWEIGHT

One of the most widespread species in the eastern U.S., white oak (Quercus alba) provides a variety of ecosystem services: wildlife habitat and food sources, watershed health and climate mitigation.

One of the most widespread species in the eastern U.S., white oak (Quercus alba) provides a variety of ecosystem services: wildlife habitat and food sources, watershed health and climate mitigation.

White oaks are bountiful mast producers — some trees can produce between 2,000-7,000 acorns per year — serving as a substantial food source for wildlife such as blue jay, black bear and wild turkey. The tree’s bark is very flaky and has a lot of surface area. In fact, a study of the species in the Mid-Atlantic found that white oaks provide habitat for more than 500 species of moths and butterflies — more than any other woody plant in the region.

“From a mast production and habitat perspective, it’s probably the most ecologically important species in the eastern United States,” says Eric Sprague, vice president of forest restoration at American Forests.

White oak trees can reach more than 100 feet tall and 4 feet in diameter, an impressive size that helps sequester large amounts of carbon. The abundance, deep roots and broad canopies of white oak also mean the species plays an important role in producing clean and steady streams of water and providing aquatic wildlife habitat. Factor in that some white oaks can live for many centuries, thus offering benefits for generations of people and wildlife. Yet, one often misunderstood and under-recognized, but profoundly important, benefit to people is the use of white oak as a forest product.

VOLUME = VALUE

American white oak has a broad range of uses, from construction-grade products, like railroad ties or wood pallets, to high-quality materials such as flooring and veneer for cabinets and furniture. According to the American Hardwood Export Council (AHEC), all of the sub-species that are classified as American white oak together account for roughly one-third of the American hardwood resource.

The wood properties of white oak made it commercially successful over the centuries, and it is still one of the most exported hardwood species in the U.S. today. But the status of white oak is beginning to change, and the focus on sustainable management and harvesting is more integral than ever in the production of white oak wood products.

“It’s been a species that has been maintained in the forest system up until now,” says Jeff Stringer, Ph.D., professor and chair of the Department of Forestry and Natural Resources at the University of Kentucky.

Working in the forestry field since 1981, Stringer has spent most of his career researching management techniques that increase the volume, and ultimately value, of white oak. His first project began in 1983, and he and his team are still monitoring progress today.

Stringer and other researchers are experimenting with different thinning treatments, such as removing small trees from competition, to determine if they could accelerate white oak growth and ultimate value. They have found they could significantly increase the growth and quality of white oak trees, resulting in price increases.

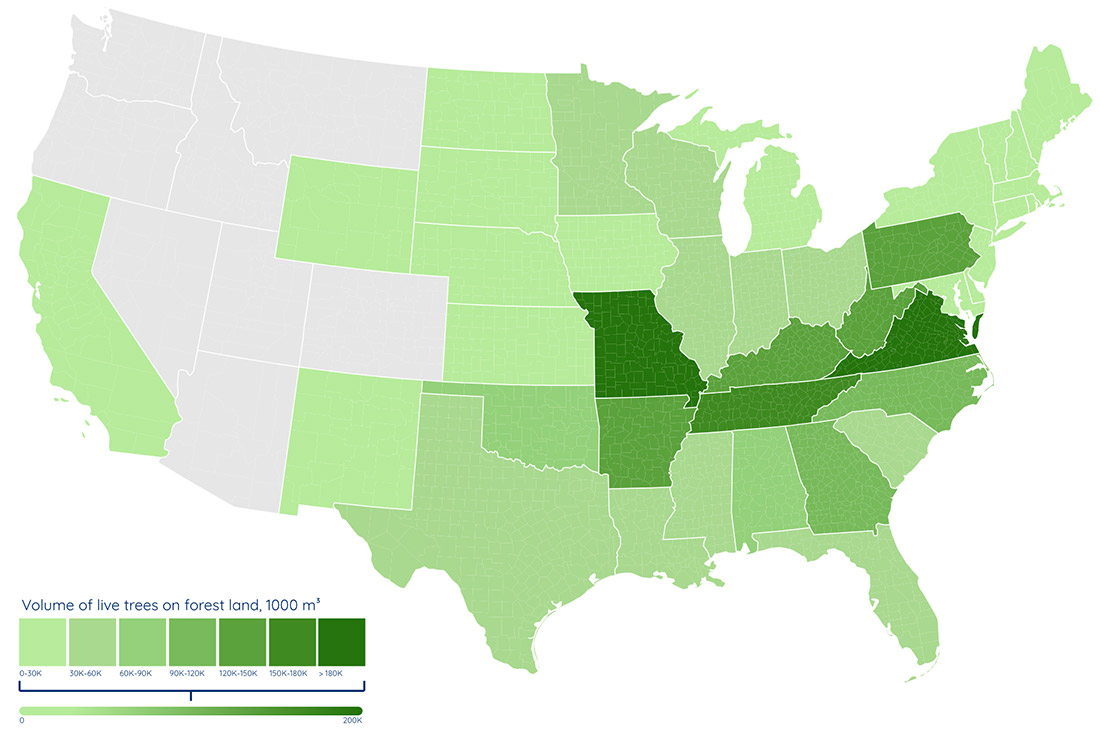

While white oak has historical significance, Stringer’s testing sites are in one of the richest parts of the central hardwoods region, spanning from Missouri to Pennsylvania, where white oak is the largest species by volume.

Volume and value go hand-in-hand in Kentucky, where white oak is the leading species exported out of the state. The 2017 numbers for Kentucky are on par with national figures from AHEC, with the state boasting $347 million in wood-related exports, nearly one-third (or roughly $100 million) of which are the most exported product of them all: barrels.

A COOPER’S CRAFT

Humans have used wood barrels for millennia. From storing and processing food items to transporting goods over long distances, a barrel’s utility is ultimately driven by its sturdiness and durability. White oak in particular also has tyloses, bubble-like structures in the heartwood that make the wood and products made from it impenetrable to liquid and decay.

Yet, in the advent of cardboard and steel in a world of mass production, barrels have become much rarer, except for in a few industries that would be entirely different, if not out of business, without white oak barrels.

Independent State Company (ISCO) was founded in 1912 by T.W. Boswell, who had some forest land in southern Missouri near the Mark Twain National Forest and decided to harvest the white oak on his land as staves to build barrels. Now in its fourth generation (the fifth has begun working in the cooperage, too) as a family-owned business, ISCO has an illustrious history, from the woes of Prohibition to being at the forefront of the burgeoning American wine industry in the 1970s and 1980s. Through it all, ISCO has become a world renowned cooperage, with facilities on four continents and a booming business to show for it.

When it comes to casks that will hold precious contents like wine or spirits, even the smallest margin of error can create major problems. While automation is certainly a factor in crafting barrels, it’s actually the combination of machinery, technology and, most importantly, the skills and craftsmanship of ISCO employees that ensures barrels meet the company’s high product standards.

“It’s very hard to automate what we do,” says Brad Boswell, great-grandson of T.W. Boswell and current CEO of ISCO, “there is still an enormous human element to it.”

At both the sawmills and the cooperages, every piece is handled by a human being. Defects in white oak are very random and hard to inspect, so it takes a lot of skilled people.

“Because white oak has such a great amount of variability,” Boswell says, “we like to say that our number one job as coopers is to take a very inconsistent raw material and make a very consistent barrel that distillers and winemakers can count on barrel after barrel, year after year.”

ISCO employs the philosophy of providing the best products to its clients, and in the end, employees incorporate time-tested, traditional techniques in their work, harking back to the era when the company was founded.

“Our associates view themselves more as craftsmen than as production workers,” Boswell says “Most people would tell you it’s satisfying to make decisions that affect the quality of our barrels. People take great pride in that work.”

CHEERS TO THAT!

The fruits of that labor find their way into a glass. But before the alcohol hits the bottle, winemakers and distillers are constantly figuring out how to enhance and adjust the taste of their product, which oftentimes puts the barrel front and center.

“Winemaking is a wonderful mixture of art, science, craft and imagination,” says Eric Aafedt, the director of winemaking at Bogle Vineyards in Clarksburg, Calif. “A lot of it is blending and tasting. A lot of that comes with barrel types.”

Bogle ages nearly all of its wine portfolio in barrels, for a year on average. Barrel-aging concentrates the flavors and colors and creates a softening and complexity out of the wine, and a fruit-forward driven style from esterification. Common flavors that are derived from the toasting profiles Aafedt creates with the cooper are vanillin and eugenol.

“The actual aging of the wine in a barrel does create a much more complex wine,” he says. “It’s a real belief that I hold that barrel-aging makes a big difference in quality.”

The process is similar for distillers, like those at Michter’s, a Lousiville, Ky.-based, American whiskey distillery that traces its roots back to 1753.

Michter’s products average about six years of maturation, a process managed by Andrea Wilson, the company’s master of maturation. Wilson’s grandfather was a known moonshiner in Kentucky, so it was inevitable she’d end up in the business — and good thing, she knows her stuff, and knows how important white oak is to the process.

Like Aafedt, Wilson works with coopers to create flavor profiles. She and her team look for vanillin, which is extracted from the wood’s lignin layer, and caramelized sugars that derive from the breaking down of the hemicellulose layer. For bourbon specifically, the type of wood is essential. Congress passed a law in 1964 that designated bourbon the national spirit of the United States, and also outlined criteria that bourbon must adhere to, among which is requiring aging in new, charred oak barrels.

“Even though the law only requires new charred oak,” Wilson says, “there’s tremendous value in using American white oak.”

CAUSE FOR CONCERN

White oak’s popularity around the world is such that white oak lumber export values increased by 24 percent, up from $410 million in 2016 to $509 million in 2017, according to the American Hardwood Export Council. Using U.S. Forest Service data, the council has also found that American white oak growth exceeds harvest in all major supplying states.

That said, folks like the University of Kentucky’s Jeff Stringer forecast long-term loss of white oak dominance in the central hardwoods region.

“All the data points to a fact that there’s going to be a diminished amount of white oak in the system over time,” Stringer says. “That’s a long-term sustainability issue.”

Potential threats include usual suspects like land use patterns, forest fragmentation and pests and disease, but the real challenge facing white oak is difficulty naturally regenerating.

While white oaks are one of the most abundant tree species by volume, when looking at the forest floor, white oak seedlings are becoming rarer and rarer, or absent in some cases. White oak abundance can be attributed to past land use disturbances, from logging to severe wildfire, that created conditions where white oak thrived.

Natural, low-intensity fires that would eliminate other tree species like maple, which are more susceptible to fire, have been so rare that the forests are becoming more favorable to other species than white oak. When shade-growing species, such as red and sugar maple, become the dominant canopy species, white oak seedlings are locked out of the next forest.

Improper forest management plays a part, too. For example, when loggers select the biggest and tallest trees, the genetic diversity and quality of the trees within the stand is reduced, leading to degradation of tree quality over time. The possibility of the reduction of white oak supply and quality isn’t just being felt by the forest products industry, but also the winemakers and distillers who rely on barrels for their livelihoods.

For the folks at Michter’s, the thought of white oak production declining is of serious concern.

“Both as Michter’s and as an industry, it’s not something we brush off and take lightly,” Andrea Wilson says. “It’s something very important for the sustainability of our business. It’s a very important raw material for us. We can’t make Kentucky bourbon without it.”

Michter’s Master Distiller Pam Heilmann believes that conservation and reforestation are important for future generations to enjoy the benefits white oak forests provide. But with two decades of industry experience, she also understands that business depends on a reliable supply of white oak.

“You’ve got to ask yourself ‘OK, this industry is booming, and that’s wonderful, but is that sustainable for the future?’,” she says. “Who’s thinking about that?”

A WAY FORWARD

U.S. Forest Service, to implement sustainable management

and restoration activities to ensure future success

for white oak across the central hardwoods region.

Because American white oak is such a slow-growing species, it is really important to ensure there’s not a large gap in timber supply or ecological benefits. That said, without disturbance, we won’t have white oak forests in the future.

In other parts of the United States, prescribed fire is a useful disturbance technique to ensure forest health. However, in the eastern U.S., prescribed burns aren’t necessarily the answer. These areas have more adjacent population centers, face cultural challenges to wildfire, and lack the infrastructure needed to contain a burn. Prescribed fire could be one of those tools used where it’s appropriate, but sustainably managing and harvesting white oak forests is the best way to create ideal conditions — in both an ecological and economic sense.

“It’s a perfect marriage of sustainable forest management and creating conditions that sustain all the benefits of white oak for the future,” says American Forests’ Eric Sprague.

To help landowners adapt forest management practices to sustainably grow and harvest white oak, with natural regeneration in mind, the White Oak Initiative was created. The group — comprised of nonprofits, government agencies, academic institutions, the wood products industry, and wine and spirit companies — is leveraging resources, exchanging research and implementing initiatives to ensure white oak remains the viable resource it is today.

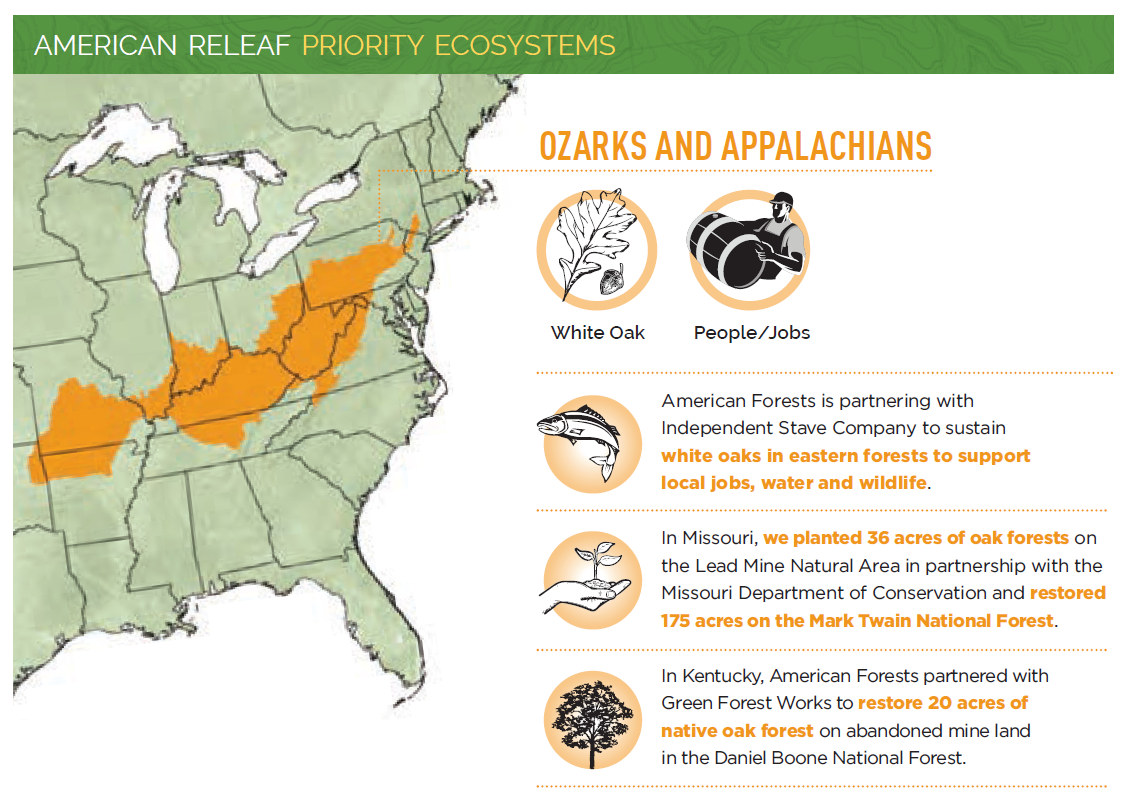

For Sprague and American Forests, white oak restoration is a top priority, not just for the aforementioned ecological services the species provides, but also the impact it has on people and communities. To meet this objective, American Forests has identified the Ozarks and Appalachians — essentially all of the central hardwoods region — as a priority American ReLeaf landscape and has already been hard at work participating in restoration activities across the region.

“We’re excited about how we can use restoration to create those ecological benefits in combination with the people benefits,” Sprague says.

White oak is such an important economic resource across the eastern U.S., particularly in rural areas, where jobs are important. The clock is ticking to maintain the immense benefits white oak forests are providing today, while simultaneously planning for the future.

“We have some time to figure this out because white oak isn’t going away any year now,” Sprague says. “But if we don’t start now, there will be challenges in the future.”

Christopher Horn writes from Washington, D.C., and is the director of communications at American Forests.