High in the Rocky Mountain forests, a bird and a tree have relied on each other to thrive in harsh conditions. As one of them faces catastrophe, both may need new strategies for survival.

By Jared Bernard

On the slopes of the subalpine zone of the Rocky Mountains, where the forested mountainsides give way to the treeless alpine mountaintops, a tree and a bird — whitebark pine and Clark’s nutcracker — repeat the steps of a dance they have danced for centuries, each helping the other species survive. But, the steps of the dance are becoming more difficult. A catastrophe is silently unfurling there — one that has the potential to unhinge the subalpine zone’s fragile community of organisms. The hardy, sprawling whitebark pine is now under siege from two battlefronts: a fungus and a beetle. If the whitebark pine loses the battle, it will have cascading effects for the entire ecosystem.

THE DANCE OF THE NUTCRACKER AND PINE

Whitebark pine (Pinus albicaulis) is a white pine, having bundles of five needles. Often forming the “krummholz” forests — those whose trees are stunted and deformed as a result of surviving in harsh, exposed high elevations — these trees comprise the sparse canopy that protects the understory species. The whitebark’s nutritious seeds, which contain 21 percent protein and up to 52 percent fat, are essential to a community of seed-eating animals. The pines produce cones in huge quantities every two to three years, during so-called masting years. When that happens, every animal in the vicinity gorges on their seeds.

In particular, the whitebark pine has evolved a mutualistic relationship with a remarkable bird called the Clark’s nutcracker (Nucifraga columbiana). As if agreeing to terms in a contract, the whitebark pine relies almost exclusively upon the nutcracker for the dispersal of its seeds, and the nutcrackers owe a large part of their winter diet to the seeds from the whitebark’s thick-scaled cones, which they hammer open with their speciall adapted straight, black bills.

Teresa Lorenz is an expert in these species’ delicate relationship — studying their association by attaching an antenna to the birds. At the University of Idaho-Moscow, she uses radio-telemetry to study caching behavior in Clark’s nutcrackers. She describes how, each autumn, a nutcracker decides whether to become a resident of an area or emigrate away depending on the availability of whitebark seeds. According to her radio transmitter, resident nutcrackers make up to 10 trips per day to harvest and cache whitebark pine seeds, and each trip can be up to a 32-kilometer flight.

“But the mutualism between the nutcracker and the whitebark pine is inefficient,” Lorenz explains. Whitebark pine seeds don’t survive digestion, so being a major food source for many animals doesn’t actually help them germinate. They must be planted by a Clark’s nutcracker and then forgotten. The trouble is that nutcrackers have exceptional memories. They’ll cache tens of thousands of seeds and remember almost all of them for up to nine months. The whitebark’s lucky break is that, like an insurance policy, the nutcrackers tend to cache twice what they need to survive a winter.

That’s great except that in the eight sites of the Olympic and Cascade Mountains studied by Lorenz, her radio-telemetry has caught the nutcrackers red-handed caching whitebark pine seeds in all manner of places unsuitable for germination. These seeds require lots of light and cool temperatures, yet at Lorenz’s research sites, most of them are cached in lower elevations and under the dense canopy of other conifers, crowding the little seedlings with plenty of competition. She suspects that the nutcrackers do this to avoid having their caches buried under snow. To that end, she finds that when nutcrackers do cache seeds in this region’s whitebark-friendly high elevations, they usually stick them in treetops. “The nutcrackers statistically avoid caching in open areas or burns” — the very conditions ideal for whitebark pine — which could be to avoid predation by hawks, she says.

Between those that get eaten and cannot germinate, and the survivors that end up in unsuitable spots, ultimately “only 16 percent of whitebark seeds can potentially germinate” in these areas.

Lorenz explains that because a whitebark pine produces an average of a million seeds over its lifetime and only one is necessary to replace its parent, 16 percent would usually be more than enough. Now, though, the whitebark pine is under assault from two tenacious enemies.

WHITEBARK UNDER THREAT

The first of these enemies is a fungus, Cronartium ribicola, which causes the disease white pine blister rust. Its peculiar life cycle is split between five-needled pines like whitebark pine and currents, gooseberries and other plant hosts.

In the late summer, the rust forms a canker on the pine’s bark, below which fungal filaments burrow to extract nutrients. Once this fungus is pollinated by insects, it forms its eponymous pale yellow blister in the springtime. The following summer, the blister bursts and the fungus beneath it moves from dead tree tissue into the adjacent living bark — so the rust spreads like necrosis over the whitebark pine. The disease causes branches — sometimes cone-producing branches — to die by preventing water and nutrients from reaching them. If the main trunk is affected, the tree will die. “It’s like a living, but unproductive creature. It’s like a zombie tree,” says American Forests Science Advisory Board member Dr. Diana Tomback, an ecologist at the University of Colorado-Denver.

The fungus won’t spread to another tree from there, but that doesn’t mean nearby trees are safe. This is where the gooseberries and other understory hosts come in. When the blister bursts, a puff of yellow spores is released onto these hosts, and in the late summer and fall spores are released, infecting other pines. In this way, the fungus lives out its lifecycle — from pine, to gooseberry, to pine.

Dr. Tomback is the director of the Whitebark Pine Ecosystem Foundation, a nonprofit organization started in 2001. She started working on whitebark pine back when their populations were much healthier. “Now, you’ll see a stand that’s got cones and nutcrackers all over it,” she says, “but come back in five years and you’ll find them dead.”

Monika Maier is a University of Utah researcher surveying seed-harvesting patterns for populations in Glacier National Park. In some of Maier’s populations, every single tree is infected with blister rust. “The trees infested by blister rust die eventually, perhaps over several years,” Maier says soberly.

Even areas with relatively little blister rust may still be subjected to another threat. Enter the mountain pine beetle (Dendroctonus ponderosae), the notorious tiny beetle that remains the scourge of forestry in the Pacific Northwest and beyond. They burrow their way en masse into a mature pine to devour its phloem — the layer of underbark that carries a tree’s nutrients — as well as its soft pro-cambium layer that generates new wood.

The beetles release pheromones that attract others, so even if the victim is able to endure the initial attack, it will soon be engulfed by another onslaught. Tiny pores on the beetles’ mouths are laced with blue fungal spores that grow to invade the wood, staining it blue and damaging the xylem — the pathways through which the tree carries water. Ultimately, the pine dies from dehydration and starvation. Mountain pine beetles have killed scores of whitebark pines and, sadly, these beetles affect the few older, cone-producing trees resistant to blister rust.

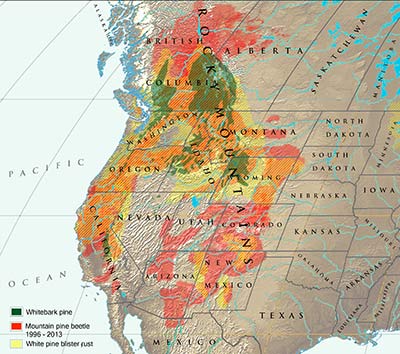

In 2012, Lauren Barringer, another University of Colorado-Denver researcher, Dr. Tomback and others published an assessment of specific areas of whitebark pine in Montana’s Glacier National Park, Alberta’s Waterton Lakes National Park and the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. In the areas studied, the mountain pine beetle was found to be attacking at least six percent of the whitebark pine in Glacier National Park and the adjacent Waterton Lakes National Park across the border in Alberta. Add in white pine blister rust and the picture becomes even bleaker: “The Glacier/Waterton Lakes area is disturbing,” Dr. Tomback laments. “There is up to 100 percent die-off. You’re hard-pressed to find a tree without a canker.” To the south, in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, they found that 35 percent of whitebark pine is already dead as a result of the combined threats of beetles and blister rust and an additional 38 percent is currently under siege by beetles and may soon join them.

THE FUTURE OF THE PINE-NUTCRACKER DANCE

Lurking behind the scenes like a puppeteer is the biggest enemy to the survival of whitebark pine: climate change, which leaves trees more vulnerable to diseases like blister rust and has had astounding effects on the beetle population.

Mountain pine beetles require warmer temperatures for productivity, so their populations are usually kept at bay by severe winters in the high elevations of the Rockies. Since the outbreak began, the beetles have massacred 45 million acres in British Columbia and more than 3 million acres in west-central Alberta. They’ve now metastasized to destroy millions of acres in the United States as well, including the Greater Yellowstone Area. In total, more than 41 million acres of U.S. forest are estimated to be dead or dying.

Considering the close alliance the tree has with the Clark’s nutcracker, the precipitous decline of the whitebark pine begs the question of the nutcracker’s situation. But all data seems to point to the nutcrackers getting along just fine.

Dr. Joyce Gould, the science coordinator for Alberta Tourism, Parks and Recreation, and a board member of the Whitebark Pine Ecosystem Foundation in Canada says flat out: “I think the nutcrackers don’t go into decline because they switch their food source.”

Dr. Gould confirms what Dr. Tomback has seen: The nutcrackers aren’t entirely dependent on whitebark pine seeds. They also enjoy summer fare of insects and will eat seeds from other conifers. Clark’s nutcrackers even take — or sometimes beg for — handouts from campers. Thus, researchers aren’t seeing a decline in the nutcracker that mirrors the decline in the whitebark pine.

Nonetheless, Maier believes that the nutcrackers begin to avoid places that whitebark pine has disappeared. She relates that in places like Glacier National Park, whitebark pine seeds may be the nutcracker’s primary food source, especially during winter, and it’s in places like this she fears a localized decline in Clark’s nutcracker.

The moribund whitebark pine itself has earned a conservation status of “Vulnerable” with the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and is listed as Endangered under Schedule 1 of Canada’s Species At Risk Act (SARA).

In the United States, the whitebark pine’s status is more complicated. In 2010, the species was proposed for Endangered or Threatened status, but a year later, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service tabled it, calling it “warranted but precluded.” This means that the whitebark pine meets all the criteria for federal listing, but the title is withheld. This decision is the result of too many other species being deemed “higher priority” and jumping the queue ahead of whitebark pine, leaving no resources available to assess its status.

“Currently, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has ordered due dates through 2016,” says Mark Sattelberg, the officer coordinating the whitebark pine’s case in the Wyoming Field Office in Cheyenne. “That does not mean the work stops on the whitebark pine.” As a candidate species, its case must be reexamined each year.

“As the other species are completed, the whitebark pine will move up the priority list,” he says. When that finally happens, the Fish and Wildlife Service will take the IUCN and SARA listings under consideration, but will pay more attention to proposed recovery strategies.

STRATEGIES FOR RECOVERY

Such a strategy was released in June 2012 by American Forests Science Advisory Board member Dr. Bob Keane of the U.S. Forest Service’s Missoula Fire Sciences Laboratory, another member of the Whitebark Pine Ecosystem Foundation board. “I don’t think the lack of listing has affected the restoration efforts one bit,” Dr. Keane says earnestly. “Restoration comes down to money and, as far as I know, there won’t be any additional monies for restoration once the species is listed.”

The recovery strategy outlines tactics on multiple scales, from the entire trans-boundary range of the whitebark pine to provinces and states, forests and even individual trees. Dr. Tomback, the strategy’s second author, stresses the importance of planting rust-resistant seedlings. In whitebark populations, some individuals will happen to be more resistant to rust. Collecting seeds from those trees and growing seedlings in special facilities like the Coeur d’Alene Nursery in Idaho will augment the number of trees in a population that have resistance to blister rust.

As the climate continues to change, the seeds collected from one population unfortunately may not produce seedlings that are adapted to the same location several years from now. To counter this, computer models will predict the regional climates in the years to come so seeds can be distributed accordingly by agencies and organizations like American Forests.

Individual trees will be protected from mountain pine beetles by using the deterrent verbenone, a natural chemical released by trees overwhelmed by bark beetles. Applying it to healthy trees confuses potential attackers into thinking the tree is already destroyed, so they move on. Verbenone proved useful against the southern pine beetle that was impacting the forestry of the southeastern U.S. and is so far proving helping in the fight for the whitebark pine.

“The best thing the strategy does is recognize the need for trans-boundary coordination,” Dr. Keane says. Dr. Tomback adds that working together on whitebark pine recovery will benefit both nations. “It behooves us all in this time of economic uncertainty to coordinate and share our efforts,” she implores. Otherwise, the fragile and mysterious array of life at the tree line of the Rocky Mountains will vanish.

Jared Bernard is an Edmonton-based freelance writer with a Bachelor of Science in ecology and evolution. His work currently appears in Natural History and The Gardener for the Prairies.