By Doyle Irvin

CALIFORNIANS: WE DON’T ALL SURF. We do, however, all drink the water — the supply of which is reliant on healthy forests. Until recently, it was largely understood that there is no truly ubiquitous experience here in California, besides death and (state) taxes. The state is large enough and diverse enough to seemingly lack a unifying thread. However, the truth is that wildfire has now directly or indirectly impacted every resident of our state — even those insulated by massive urban areas and their own considerable personal resources.

I spoke to Silicon Valley CEOs, self-described nerds who found themselves in gas masks on their way to work, suddenly confronted by the outdoors. I spoke with Hollywood types who washed the ash off their cars on the way to a sound stage. I spoke to people whose towns had been burnt to a husk. I spoke with elderly evacuees, retired in rural communities, counting their blessings that they got out in time. Finally, I spoke to the folks on the ground trying to prevent wildfire catastrophes from happening again.

A HOME IN PARADISE

Dave Derby is the unit forester for the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection’s (CAL FIRE) Butte unit. His team is responsible for enforcing the Forest Practice Rules and the vegetation management program. He’s been living in Butte County for 14 years and has experienced firsthand the frustrations — and consequences — of forest management, or lack thereof.

“My home is in Paradise,” Derby said. “Every home on my street was burned, except for mine. I’m not sure why mine survived.”

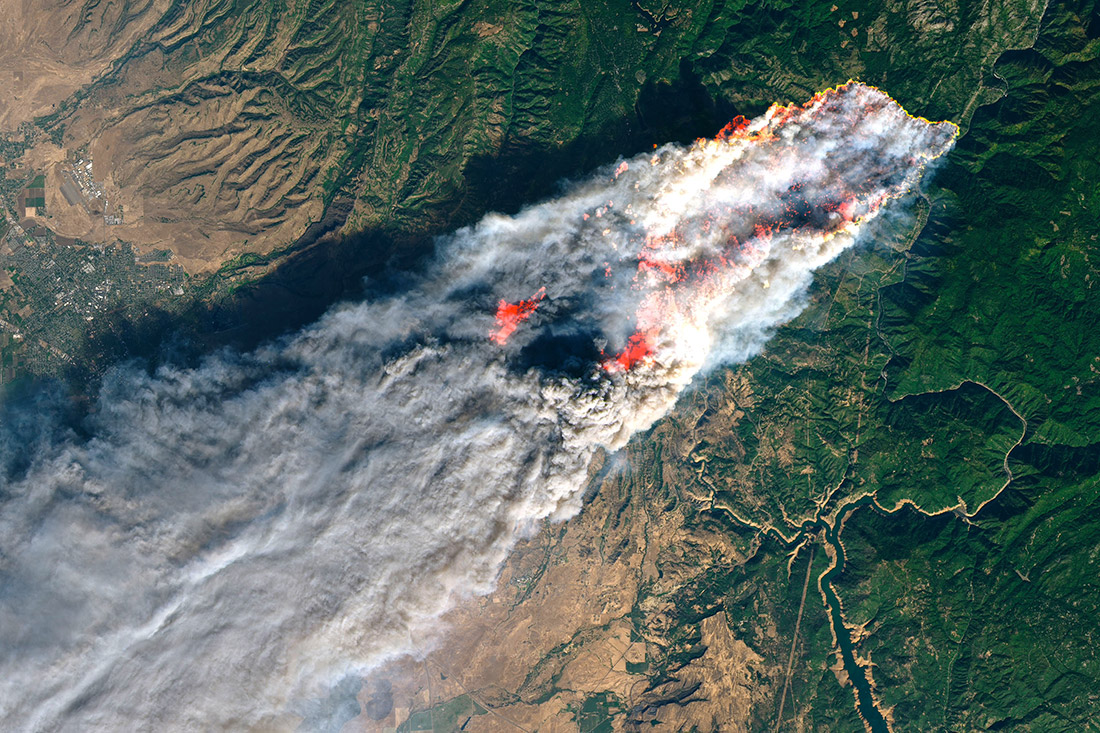

Derby’s experience is but one of many — many of CAL FIRE’s employees have left to fight a fire only to return home to a destroyed town. More than 18,000 structures were destroyed in 2018’s Camp Fire, causing $16.5 billion in damage. And while it was the deadliest in state history, it was just one fire. The state has averaged 7,777 fires per annum since the year 2000, according to the National Interagency Fire Center.

“A lot of these timbered communities, they’re in shock,” Derby added. “Especially the ones that lost their homes.”

SPURRED INTO ACTION

This direct experience with wildfire is galvanizing Californians into action. I spoke with camp director and volunteer firefighter, David Bunnett, who lives in South Lake Tahoe. His camp is on Fallen Leaf Lake, which in 2007 nearly succumbed to the Angora Fire.

“We evacuated the 300 or so guests in about 15 minutes, and six or seven of us stayed on site,” Bunnett said. “I was actively fighting the fire, up on the ridge, and we managed to contain it there.”

The Angora fire burned 3,100 acres, and destroyed 242 residences, but they success- fully managed to contain it before it reached the camp Bunnett directs. But even with “success” (he probably wouldn’t call it that), Bunnett realized they had to change how they interacted with the environment.

He brought back the 60 staffers and spent a week drastically improving defensible space. His staffers are all college students up in the mountains for the summer, and their normal duties might include arts and crafts, hiking, leading youth group activities — they had never used trimmers before.

“There’s a realization when you watch a 300-foot flame coming off the top of the ridge, you understand that you have to be a lot more proactive about fuel reduction,” Bunnett said. “We were already pretty good about tree removal, because we didn’t want dead trees to fall on campers. For us, it was more just years and years of neglect with brush clearing.”

As I’ve seen with all of the conversations I’ve had across the state, once this realization happens, there is no returning — and that is one of the Pyrrhic victories we can attribute to the last few years of catastrophic wildfires: everyone now understands that we do need to actively manage our forests.

A SHIFT IN PERCEPTION

Brittany Dyer, American Forests California State Director, shared with me the history of forest management in our state.

“The tree mortality and drought situation have put us in this pendulum,” Dyer said. “We’ve seen natural resource management swing to the right, arguably too far to the right, and then we pulled back to the left, arguably too far to the left. And right now, we are able to see the results of our past decisions — the human decisions that have created the forest condition.”

Her point about left and right reflects my experience with the various people I spoke to about California wildfires. There’s a growing willingness to put politics aside and only pursue agendas that look at all the moving parts in a particular landscape/ecosystem.

“Not all fire is bad, and not all trees are good,” Dyer said. “It’s a middle ground and depends on the landscape/ecosystem — a constantly moving target.”

In my conversations with Mark Egbert, the district manager for El Dorado County and the Georgetown Divide, he mentioned that there’s been a shift in how people interpret his work. One of the recreational attractions in his area brings in roughly 30,000 people every summer, and the nature of the questions he gets has changed in the last four to five years.

“A couple years ago it was ‘What are you guys doing? You’re destroying the environment’,” Egbert said. “Now, you have hikers, bikers, fishermen, and they’re coming up to us and asking ‘How are you doing this? How can I do this in my area? You guys are doing a really good job and I understand it now, I know why it’s happening’.”

This kind of feedback is really motivating for him and his team. It is true that the state is being catalyzed, and the lion’s share of this momentum comes from the blatant necessity.

“I’m looking a ta mountain right now where the entire ridge, as far as I can see from left to right, is covered with ponderosa pine mortality — about 98 percent,” Dyer told me while I was on the phone with her. “The sense of urgency has erupted. Now, with this social and political momentum, we must actively man- age our forests and intentionally create our desired conditions, or by default we compromise the future generation’s health and safety.”

The good news is that the actions we take do impact the outcomes of our environment and the ecosystem services provided.

PROTECTING OUR FUTURE

Education is a huge part of these efforts. I spoke with Jennifer Szelinga, the director of the Sacramento Tree Foundation. A large part of her responsibilities is funneling the new influx of volunteers who just want to help, however they can.

“We get a lot of calls where that person feels that giving money is not enough,” Szelinga said. “You see on TV the massive destruction of the trees, but you don’t really think about what happens to them afterward, how they might regenerate — or if they do at all.”

One of the programs her foundation runs is called Seed to Seedling, and it directly addresses this. Volunteers pair up with teachers of third and fourth grade classes who have prepared a special curriculum, and the groups go out and collect acorns native to regions that have been affected by catastrophic wildfire. The students then grow the acorns into seedlings, eventually planting them in affected zones, all the while learning about healthy forests.

Actions like these make a difference, there’s no denying it. Organizations like Szelinga’s came to the Angora Ridge 12 years ago, and a healthy forest is now well on its way to replacing the unhealthy one that preceded it. Bunnett tells me that the firefighting station he volunteers at has now mostly gone professional, as the local community rethought how it managed its land and services. However, not every county that needs this kind of focused attention has the resources to provide it. Large swathes of vulnerable forests still depend on understaffed volunteers to protect them.

The question is not whether the actions we take will positively impact our ecosystem. The question is also not whether there is the willpower in our state to solve this problem. From the urban centers in Los Angeles and San Francisco, to the mountain communities like Paradise and Lake Tahoe, there is a deep understanding that something needs to be done. The make-or-break is whether or not we can move from being mostly reactive, to mostly proactive. It’s about whether or not we can organize the bewildering amount of resources available to our state in an effective manner. The fact that former governor Jerry Brown and current governor Gavin Newsom are both on board is vital, but state processes often operate slowly.

This is where American Forests comes in, and why Brittany Dyer is so excited to be a part of the team — she joined at the start of 2019. As a national nonprofit, American Forests is able to act and organize a ta pace and scale that can make a difference.

“There’s a role for our nonprofit to bridge discussions from coast to coast, from the Atlantic to the Pacific,” Dyer said. “The moment in time is now.”

Doyle Irvin has been hiking through California forests since he learned how to walk and is a contributor to American Forests Magazine.