Sewage in our rivers? Yuck!

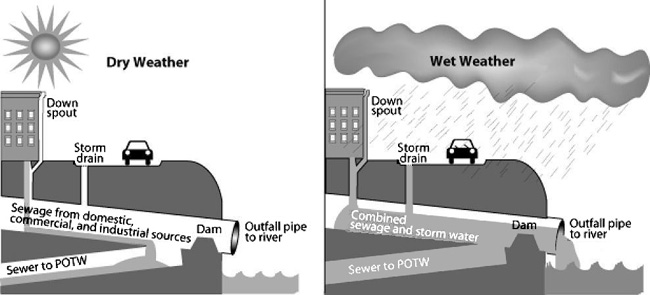

I was really disturbed when I learned a few years ago about combined sewer systems — where sewage and rainwater is collected in one pipe system — and just how many cities have these. Although no longer built into new communities, more than 770 older cities still use their combined sewer that was built back in the day, including my own city of Washington, D.C. Combined sewers may have once been thought to be convenient for urban landscapes, as they collect the wastewater from your toilets, the wastewater from industrial sites and the water that drains from rooftops and roads after rainfall (called stormwater) and take all this combined water to a facility for treatment. Everything is treated at once and then is more “safely” disposed of into a nearby stream or river; the fish can continue to swim along safely, and you can continue to wade around without much thought. Makes sense, right?

With a small amount of rain, this system works just fine. Combined sewers are built to handle the average amount of water flows. The catastrophic issue, however, is that during a large rainfall or snowmelt event, the volume of stormwater often exceeds the capacity of the sewer pipe. And, to prevent pipe breakage or sewage backup, as part of the plan, Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) areas are designed to allow a portion of the untreated combined wastewater to overflow into the nearest stream, river or lake.

Talk about water pollution! These CSOs allow not just human waste (in case that wasn’t gross enough), but all sorts of industrial waste, toxic materials and debris to go directly into our environment. Thus, they are a major source of ecological problems and human-health concerns. In a December 2001 report to Congress, the Center for Marine Conservation states that “ome of the common diseases include hepatitis, gastric disorders, dysentery and swimmer’s ear. Other forms of bacteria found in untreated waters can cause typhoid, cholera and dysentery.” Eww.

Well, at least some cities are trying to improve this. Last week, it was very exciting to read that the EPA signed off on Philadelphia’s $2.4 billion green plan to stop sewer overflows in what the E&E News calls the “strongest endorsement yet of the green infrastructure technology.” With the extensive use of green infrastructure — grass, trees, porous pavement and retention ponds — this will make Philadelphia’s new initiative the first nearly “all-green” plan for addressing sewer overflows.

So, how exactly do trees help? As we reveal on our Forests & Cities page, rather than rainwater falling directly onto rooftops or pavement and rushing into the sewer, trees intercept this water first, and less water ends up in the pipes. With more trees planted, even less stormwater will enter the pipes, eliminating the need to overflow into the local stream or river!

In the next few weeks, the EPA will unveil a new regulation expected to promote the use of green infrastructure and require new developments to absorb rainfall rather than letting it rush into overburdened sewers. There is hope that the increasing support for green infrastructure will help avoid the water pollution caused by combined sewers. I’m looking forward to the day when I can enjoy a large rainfall and not be concerned about the horrible consequences it may have on the local waterways.