By Charles Elliott

Originally published in 1945 in American Forests, Vol. 51, No. 10.

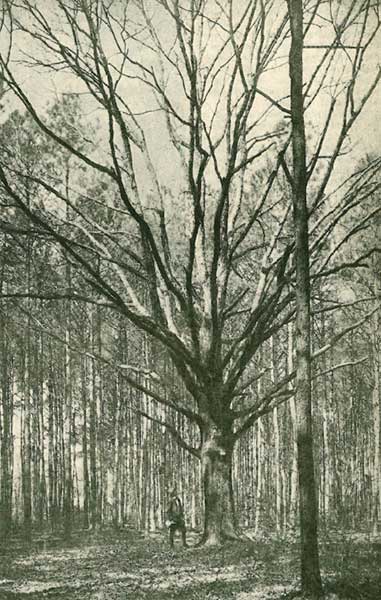

In almost every sweep of woodland, there is a certain type of tree that foresters call a “wolf” tree. Specifically, this example of avaricious flora is a side-crowned perennial, towering over and shading out the other trees of the forest. More generally, it is any member of a sylvan aggregation that takes up space which the Maker has ostensibly allotted to one or more of the vigorous, valuable individuals in the forest.

To an eye quick to appraise timber values, or a hand that wields an uncompromising ax in weeding out worthless trees, the wolf tree is a forest ulcer. Its elimination is a strict principle of forest management.

All my forestry books say that! A book I once wrote makes that claim. Perhaps not in those exact words, but that is the general idea. This is not the first time I have ever had to do a reluctant “about-face” and deny an irrevocable truth.

I take the stand as a character witness for wolf trees.

I know a tree that towers on the edge of a wood. Long years ago, when I first met it, this sylvan beauty was erect and graceful, and as pretty as a young girl blossoming into womanhood. Today the ravages of the years show in the seams of its limbs. Its shoulders, slightly stooped, have been worn thin by nature’s hardest masters and most worthy friends—the sun, the wind and the rain.

That tree has lived! It is living yet, but the foliage in its crown has dwindled to a handful of leaves and many of its branches stand withered in the evening twilight. But the march of life and death across the horizon of its existence, the tiny, budding embryos it has nurtured in its bosom, the variety of creatures it has sheltered from cold and storm, are greater in number than any other tree in the forest can boast.

Its lower limbs are within reach of the ground, and I averaged once a week climbing it when I was a boy.

The first spring I noticed the tree, a downy woodpecker had drilled a home into one of its upright limbs. I climbed the trunk to have a better look and half-way to the top found a sheltered hollow, where Boreas or one of his brothers had twisted out a huge limb in the years past.

What a marvelous story the claw and talon marks on the rim of that hollow would have made! The fragment of a gray down feather clung close under a protruding scale of bark. There was a brown splotch which might or might not have been blood. The lip of the hole was worn smooth by furred and feathered bodies sliding across it, and by sharpened claws.

For several years after my discovery, I supervised that old tree in the raising of its families of the wild. I remember squirrels and screech owls and opossums. The first family of starlings in that neighborhood drove away all covetousness of prospective tenants as they noisily took possession. Those original settler starlings have multiplied into a population of thousands.

Once a bluebird timidly selected the site. A marauding black snake drove her away and swallowed the clutch of eggs. I found the snake stretched on a limb above the nest with his belly full of the tiny blue eggs in which the mother bird and I had taken so much pride. The parent birds hovered pathetically around. In my anger I hit at the snake and lost my balance on the precarious perch. The snake escaped. I wore my arm in a sling for days.

The foresters call that tree a wolf, unfit to carry its burden in the life of the forest.

Dead and dying trees have a definite place in the ecology of the woods. Without them, many species of wildlife would soon vanish. A recent survey by one of the state agencies proved conclusively that the limiting factor in the raccoon population was the number of den trees available.

Many species of birds and animals use the hollows in trees as homes or as shelters against the elements. Mice, chipmunks and squirrels store them full of acorns and other food against the long winter months when seasonal pro-visions are as scarce as was a wartime T -bone. Flying squirrels make their homes in the crevices and hollows.

I remember a campfire one night in a group of trees, which the lumbermen had rejected as unfit for the saw. More than a dozen-of the little gliding mammals were playing in the woods that night. They would scamper to the top of a tree beyond the fire, glide in a quick silvery arc over the bright flames and flap against one of the tree trunks on the other side. We could hear the miniature claws scraping against the bark as they climbed to the top of that particular tree and, after a moment, see them zip across the fire again.

The different kinds of mammals that make their homes in hollow trees, however, are few by comparison with the numerous species of birds which breed and live in these forest shelters. And birds, we learned in lesson one, are man’s best friends in the out-of-doors.

The nuthatches are one group which use the wolf trees of the forest. All species of nuthatches are valuable to man for the multitude of insects they consume.

The brownheaded nuthatch will dig his home out of a rotten limb and lay his eggs on a flat nest of such fluffy materials as wool, pine seed wings and soft, shredded bark. The red-breasted nuthatch smears pitch around the entrance to his home. The American bird is close kin to the European red-breasted nuthatch, which seals his wife in with pitch during the period she is incubating their eggs. He leaves a tiny hole in the resin door, through which he passes food and water during the three weeks she is on duty.

The wood duck selects a large wood-pecker hole or tree cavity for a nesting site. Unlike most other ducks, mamma wood duck lays her eggs many feet above the water. Naturalists have disagreed since the time of Linnaeus about how the wood ducklings get from the nest into the water. Some say the mother duck transports them through the air on her back or in her bill. Others say she pushes them out of the nest and they drift as gently as a down feather to the surface of the pond or stream if it happens to be below. There are other versions, too, which may or may not be verified.

Woodpeckers are almost universally tree dwellers. In making their homes, some of the larger woodpeckers carve them out of living trunks of the trees. Others choose dead limbs or snags of the forest. They explore the surrounding dead or decaying wood for insect larvae or grubs, their principal source of food. They help protect the living forest tree, those growing into valuable lumber, crossties and veneer wood, from the ravages of forest insects. The number of woodpecker families in a forest is necessarily limited to the number of dead snags and limbs.

Two more consumers of forest insect are the bluebird and purple martin, which make their homes in abandoned woodpecker holes. These two birds are familiar spring and summer visitors to every farm boy, where the wolf trees have been left to attract them.

While the chimney swift makes the most of civilization by using chimneys and abandoned smoke stacks in which to build his nest, in the wilderness he selects the hollow trunks of trees and sometimes the protected surface of perpendicular rock ledges. This mite of a bird, shaped like an arrow’s head in flight, builds his nest out of sticks on the inside surface of a hollow tree or chimney. He puts the sticks together with a glue made from the saliva out of his own mouth.

The crested flycatcher is another flying insect exterminator that lives in a tree hollow made and vacated by some former tenant. This superstitious bird makes a cozy nest in the cavity and lines it with snake skin, usually the cast-off skin of some reptile. Naturalists have never determined whether this is a throwback to some prehistoric past, or whether the snake skin is deliberately woven into the nest to frighten away intruders.

These are only a few of the birds and animals which live in the hollows of trees in the woods. The dead, dying and decaying trees are the most interesting places in the forest. Even the wasps and hornets, both eaters of flies and gnats, dig out decayed wood and chew it into the pulp with which they make their papery nests. Many Insect species crawl into holes and crevices to spend the winter months.

Those who know its place in the ecology of the forest will agree with me that these ugly wolf trees, these snags, these trees classified as worthless space fillers are valuable wildlife units in the vast stretch of North American woodland.

What’s become of wolf trees today? Conservation biologist Michael Gaige revisits these elders of the eastern forest in the Fall 2014 issue of American Forests, coming online October 29th.