By Darrin Youker

Forever Wild — those two words have long governed New York’s approach to protecting its forested lands in Adirondack Park. That phrase, written into the state’s constitution, is more than just a simple guideline to forestry; it is a barrier to prevent anyone from removing even a single tree from state-owned land in the park. The Adirondacks, a six-million-acre park made up of public and private lands, is as big as the state of Vermont, and the protections given to its woods are some of the most stringent in the world. Yet some believe the time has come to tweak those rules.

In the ongoing push and pull between the protection of wilderness and the need to create a sustainable economy in the park, some are looking to logging to help propel future growth. A New York State senator has proposed a bill to open up logging on a tract of land in Adirondack Park that the state plans to purchase from The Nature Conservancy; land that the nonprofit acquired from a large paper manufacturer.

New York already allows logging in state forests outside of the Adirondack and Catskill Parks. The bill, introduced by Senator Elizabeth Little of the 45th District, would also allow logging on future state land purchases. It would not apply to the state’s current 2.5-million-acre landholdings in Adirondack Park.

Senator Little, a Republican who represents much of the Adirondack area, does not want the state to buy any more private land within the Adirondack boundary, believing New York’s landholdings are large enough. Adding more land to state control, she says, would hurt the timber industry at a time when communities in the region need good, paying jobs.

However, should the state acquire any more land, Little said she wants to make sure that logging is allowed in every purchase. She believes that a better philosophy for New York to follow is to obtain conservation easements from private property owners; under such easements, timber harvesting would still be allowed, and land would remain in private control.

According to Little, communities in the region are graying, with census numbers showing that the concentration of seniors within the Adirondacks is comparable to some communities in Florida. What the Adirondacks need are family-sustaining jobs, and logging has been a base of employment for generations, Little argues: “What we are seeing is the inability to sustain a grocery store, to continue having volunteer firefighters, and we are seeing declining enrollment in our schools.”

Bringing logging to new state forest lands will be no small task. Two sessions of the New York State Legislature must approve the change, and then voters must approve amending the state constitution, according to John Sheehan, spokesman with the Adirondack Council, an environmental group that opposes the legislation. “Its chances of passage are unrealistic,” he says.

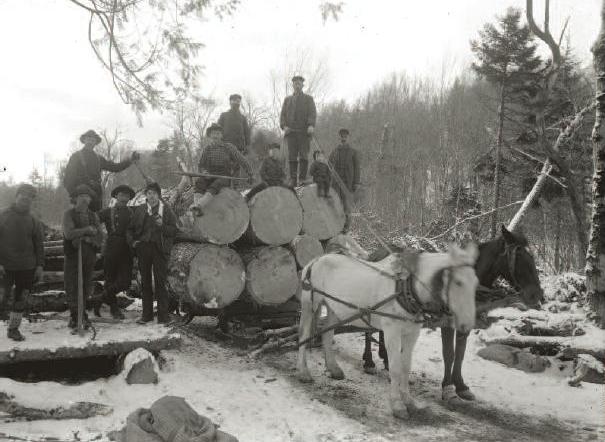

STRONG HISTORY

New York’s stringent approach to forest protection did not happen by accident. It was the culmination of a pressing need to defend a rapidly declining forest resource that protects the water supply for downstream cities. In the late 1800s, the Adirondacks were a hefty source of lumber for growing American cities. At times, lumber companies were clear-cutting vast reserves of forest and then letting the land go back for tax sale, costing communities valuable revenue, Sheehan notes. Plus, the Adirondacks are the headwaters for a number of rivers, including the Hudson, and more than a dozen cities use Adirondack water as their drinking source.

In 1892, the state created Adirondack Park, a bold move that predated the creation of many national parks. It was not a park in the traditional sense. State officials drew a blue line on a map encircling the region and set about on a course to buy properties within that boundary. Since then, there has been a mixture of public and private lands within Adirondack Park.

During the park’s early days, clear-cutting was rampant. “They were leaving behind a devastated landscape,” Sheehan says. That led to the creation of a state constitutional amendment in 1895 that banned logging outright on state lands, requiring that they remain “forever wild.”

“It is still the strongest and strictest forest protection in the world,” Sheehan claims, adding that many New Yorkers do not want to see it tampered with. “We believe there is a lot of support for the ‘forever wild’ clause.”

Sheehan believes that opening up newly acquired state forest lands could cause a drop in timber prices. Some of the land that New York wants to add to its forest system also contains some of the last old-growth woods in the park, and that habitat should be maintained.

Little believes that logging is essential to the Adirondacks, along with the support it provides to paper mills within or near the park boundary. Although environmental groups believe the state forest systemis healthy, the senator also asserts that the inability to remove downed wood or harvest old timber chokes out new growth. She believes that opening the lands to logging would encourage not only the forest but also the local economy to grow.

“Government is probably the biggest employer in the park,” Little says. “What we need is more private-sector growth. You will not get that when you make more timber lands into state lands.”

Little’s bill proposes that any logging done on state forest lands would be supervised by the Department of Environmental Conservation to ensure that the forest is managed sustainably.

ECONOMIC DRIVER

For the better part of a century, the Finch Pruyn paper company was an economic engine in Glens Falls, a small city on the Hudson River just outside the park boundary. At one time, the timber giant was the second-largest private landowner in the state. But in 2007, Finch Pruyn was looking to divest some of its landholdings.

The Nature Conservancy (TNC) stepped in, purchasing 161,000 acres of lands untouched by development in the heart of the Adirondack wilderness. Those lands contain vast tracts of forest, the highest waterfall in the park, and scenic vistas of gorges along the Hudson River. It was an acquisition heralded by environmentalists and recreation enthusiasts, thrilled that so much previously closed wilderness would be open to the public.

The TNC staff had worked with foresters at Finch Pruyn on a number of forestry conservation issues, says Michael Carr, executive director of the Conservancy’s Adirondack Chapter. That close relationship helped TNC step in on this once-in-alifetime opportunity.

The $110-million purchase gave TNC a landholding the size of 11 Manhattan Islands, spread across six different counties. The properties adjoin state lands in many places and were often devoid of any roads. A large band of marble runs across the center of the landholding, creating a rich soil that grows a number of rare plants.

“When you look at timber data on the Finch lands, it reveals that these lands are very well stocked and well managed,” Carr says. “They connect a lot of water courses and contain the headwaters of many, many rivers.”

After the land acquisition, TNC went through an 18-month process to analyze the property’s ecological value and devise a plan for how to use the resources. Working with local and state government officials, scientists, and other environmental organizations, TNC decided to sell 92,000 acres to a timber investment firm, from which state officials later acquired a conservation easement. That opened up areas for snowmobile trails, a vital economic resource for the park during the long winter months.

Of the remaining land, the consensus among those various groups was to set aside 65,000 acres of forest that represented a rich ecological resource and open up new areas for public recreation. The state has agreed to buy those lands, but the decline in the economy has delayed the purchase, Carr says. Since then, some local government leaders like Senator Little have balked at the plan, arguing the state has too much forest land already.

Since the early 1990s, according to Sheehan, the state has eyed the Finch land as a possible addition to its forest holding because it represents such a diverse habitat and provides public access to some of New York’s most scenic areas. Uneven terrain and sensitive ecological sites also make many of the areas inside those 65,000 acres unsuitable for logging. Carr adds that recreation and tourism are major economic drivers in the park, which will only increase with this land purchase. However, if Little’s bill passes, logging activity would seriously limit recreation opportunities across those 65,000 acres, as well as threaten the ecological stability of sensitive areas and fragment the habitats on which local wildlife depend.

“The Adirondacks are the best example in the world of a temperate deciduous forest,” Carr says. “These lands are critical to protecting that habitat.”

Darrin Youker is an environmental reporter from Reading, Pennsylvania, and can be reached at darrinyouker@yahoo.com.