After natural catastrophes, forests and communities heal together.

By Carrie Madren

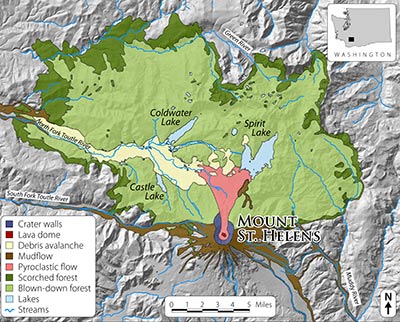

When a hurricane hits the coast or a tornado rips through the countryside, they create devastation — wrecking natural landscapes, as well as lives and livelihoods. Hurricane Katrina affected five million acres of forest across Mississippi, Louisiana and Alabama and caused more than $1.25 billion in timber damage in Mississippi alone. The 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami — triggered by a magnitude 9.2 oceanic earthquake — slammed coastlines across the western Pacific, killing hundreds of thousands of people and in some regions destroying everything aboveground, including mangrove forests. The lateral blast from the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens instantly destroyed four billion board feet of timber, and nearly 200 homes were claimed during the disaster.

Across eastern North America, winds from tornadoes and downbursts (strong downdrafts that cause damaging winds) disturb thousands of forested acres each year, devastating both conservation areas and timberlands according to a 2000 study. Foresters managing for timber may lose decades’ worth of tree growth and must scramble to salvage what’s fallen before insects and diseases claim their product.

Such events also affect wildlife communities — in both good and bad ways. For instance, while damage by ice or tornadoes may create more clearings for food sources, like berry-producing shrubs, small mammals may have more difficulty foraging in thick, downed debris. Wildlife that live or feed in trees, such as bats and birds, can become displaced, throwing the ecosystem out of balance.

As communities struggle to pick up the pieces and mourn what’s claimed by hurricanes, tornadoes, tsunamis, wildfires and windstorms, forests, too, must rebuild and sink new roots to rise from the wreckage.

HIGH WATER

Rising floodwaters can take down forests from the roots.

After the Great Midwest Flood of 1993, which caused nearly $20 billion in damage and covered 400,000 square miles, nearly all the trees in four stands of Sanganois Wildlife Management Area near Beardstown, Ill., were submerged for more than six months and died.

Whether it’s a river overflow or a coastal storm surge due to a hurricane, floodwaters can mean trouble for trees and forest ecosystems. First, floodwater currents, loaded with debris and silt, can erode the soils around shrubs and trees, exposing roots. In strong currents, debris may even strip bark from trees, uproot plants or strip shrubbery.

In addition to the initial physical impact, because many of a tree’s fine, oxygen-absorbing roots grow in the upper six inches of soil, these roots can die off as the soil becomes waterlogged. Without a robust root system, trees don’t absorb enough water and become weakened. As a result, foliage wilts or dies, and these weakened trees are a target for insects and disease.

Coastal flooding — often the result of a storm surge or hurricane — can cause significant damage by flooding freshwater areas with salt or brackish water. This saltwater intrusion can spell trouble for plants that rely on freshwater. Increased salts in the soil make it more difficult for tree roots to take up water because of changed osmotic pressure.

“The result is what’s called physiological drought. Even though there is water, the tree can’t take it up, and it’s the same as if there was no water,” explains U.S. Forest Service research ecologist John Stanturf of the Forestry Sciences Laboratory in Athens, Ga. “Under severe conditions, an already-stressed tree, such as one that has lost its leaves by shearing in hurricane winds, can’t recover and refoliate and may die outright.”

A few years after the Great Midwest Flood, land managers noticed that new shrubs and seedlings began to thrive in the affected areas, though the types of trees differed from the older, established stands that were killed by the flood. Some tree species — such as silver maple, green ash, sweet gum and black willow — are thought to be more tolerant to flooded soils than other trees like black locust, black walnut, tulip poplar, sugar maple and American beech. Regardless of species, though, it may take mature, surviving trees several years to recover from a summer of flooding according to the South Dakota Department of Agriculture.

HURRICANE WARNING

When Hurricane Katrina struck the Gulf Coast on August 29, 2005, winds of speeds up to 140 mph toppled trees and turned sand and debris into airborne sandpaper, stripping any trees or shrubs left standing of their leaves or limbs.

“Not much stands up to the highest wind speeds, except maybe live oak because of their growth habit and anchorage,” says Stanturf. “The farther inland you get, the wind energy dissipates, and you get less breakage and blowover,” he explains. “But even inland, you still get significant damage from the loss of major branches.”

Katrina’s damage extended as far north as Memphis, Tenn. A 2007 study published in Science used NASA satellite images to estimate 320 million trees dead or damaged in Mississippi and Louisiana alone from Hurricane Katrina. In combination with Hurricane Rita later that year, Hurricane Katrina was called “the largest single forestry disaster on record in the nation” by The Washington Post.

Damage inflicted by hurricanes depends on a variety of factors, including location, how the forest was managed and the age and height of a stand. While a loblolly pine plantation with trees 10 to 15 feet high may not sustain much damage, an older stand with 50-foot-tall trees of the same species would sustain more damage, according to Stanturf. In addition, because trees tend to support and protect other trees, there’s often more damage along openings in a forest, such as along roads or powerline swaths.

Beyond the wind damage, the storm surge that accompanied Hurricane Katrina damaged forests from the ground level. Sea waters surged more than three miles inland in some regions and more than 30 feet along much of the Mississippi coastline, causing the widespread damage inflicted by coastal flooding.

Forest recovery after a hurricane or other event depends on a particular forest’s management objective. Some hurricane-ravaged forests may be left to regenerate on their own, taking decades to a century to fully recover and reestablish. In some cases, cleanup is necessary to protect the forest from further destruction, as tree debris can become a breeding ground for insects and fungi. Other responses include salvage logging to recover the timber value that’s been lost and to reduce fire hazards, explains Stanturf. Seven years after Hurricanes Katrina and Rita, both replanted and surviving stands are recovering.

Though a post-hurricane or tornado forest isn’t initially the same type of forest that existed before the event, “it might develop into the same type of forest if managed well and if that is what a landowner wants and has the resources to accomplish,” explains Stanturf.

DEEP FREEZE

When heavy ice and wet snow coat tree limbs, the layers can be thick enough to break branches, twist limbs and crack tree crowns. Such an ice storm blanketed southern Missouri’s Mark Twain National Forest in 2009, snapping miles of telephone poles, limbs and trees.

After an ice storm or blizzard has passed through a forest, the first order of business is unblocking roads, especially roads that lead to residences, then clearing roads for larger vehicles. “We make sure people are safe first of all,” says Douglas Oliver, the Forest Service district ranger responsible for Mark Twain National Forest’s Poplar Bluff Ranger District. Then, trees are cleared from ditches, and workers ensure there aren’t hazardous trees or limbs dangling over recreation areas.

Similar to hurricane cleanup, timber may need to be salvaged before it rots and becomes worthless — or a breeding ground for pests. When the chainsaws stop, Oliver says, salvage teams have reported hearing swarms of insects boring into the downed wood. Such sheer volume of hungry insects can threaten nearby stands of surviving trees, likely weakened from the ice or wind.

Beyond insects, weakened, still-standing trees are vulnerable to disease and other physiological decline. At Mark Twain National Forest — where tornadoes and a 100-year flood have also occurred in the last five years — many surviving trees are more susceptible to ailments such as oak decline, which has afflicted red and black oak in the eastern U.S.

The summer after an ice storm or blizzard also can bring another danger. The layer of downed tree material can increase wildfire risk if conditions are extremely dry. Such a well-fueled fire could create catastrophic conditions to the point of soil sterilization, Oliver says.

In ice- and snow-damaged areas, trees that sustain light to moderate damage can begin to regenerate within a few years as the forest ecosystem as a whole recovers, but after the worst storms, enough biomass may cover the ground that new seedlings from natural seed banks can’t break through. After the cleanups in the Missouri forest, Oliver says that occasionally forest managers will do supplemental planting — especially if a silviculturist determines the need for more pines, for instance — but many times replanting isn’t necessary, as the forest regenerates on its own in subsequent decades.

AN EXPERIMENT IN SUCCESSION

When Mount St. Helens erupted on May 18, 1980 — triggered by a magnitude 5.2 earthquake — the explosive blast caused an enormous landslide with 600 mph winds and up to 600-degree-Fahrenheit heat across some 250 square miles of forests. What’s more, the searing heat caused snow and ice to “become the consistency of concrete, but moving at 60 mph,” reports ecologist Charlie Crisafulli at the U.S. Forest Service’s Pacific Northwest Research Station. “The landscape was grossly transformed from this coniferous forest with sparkling lakes into what appeared to be a gray, lifeless landscape.”

The variety of geophysical forces that volcanoes can unleash on a landscape includes bulldozing lava flows, rock-fall avalanches, billowing ash and gas plumes and searing heat. Typically, if trees are left standing, they are scorched.

At Mount St. Helens, even as ash and tephra (fragments of volcanic rock and lava) blanketed the landscape, the volcano’s widespread aftermath didn’t quite kill everything. Isolated individuals and oases of plants, small animals and fungi survived, becoming building blocks for re-growth. Late snow banks and frozen lakes protected some buried roots, bulbs, saplings and shrubs, and come spring, whole communities of plants and animals emerged.

Two years after the eruption, Congress created the 110,000-acre Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument, managed by the Forest Service. Here, ecological recovery has been allowed to take place at a natural pace. In contrast, land around Mount St. Helens owned by a private timber company was salvage logged, and acres were replanted with Douglas and noble fir for commercial forestry.

“Adjacent to the monument, the lands in the blast area were tinkered with, and that became a natural experiment created by the eruption and the management decisions,” Crisafulli explains. In the reforested areas, conifers now dominate the canopy, making the understory dark, with little biodiversity, but within the monument, the eruption was like a reset button for the surrounding landscape.

The first signs of life to emerge were native grasses, plants and shrubs, along with birds, small mammals and insects. “Populations were spared that served as sources for repopulation in adjacent areas,” says Crisafulli. As the landscape slowly regenerates, where trees once dominated, unique, diverse grasses, herbs and shrubs that aren’t found in other stages of ecological development are flourishing, and ecological progress is clear.

LESSONS IN RECOVERY

Researchers are still learning how ecosystems recover and how we can help forests survive a natural disaster. “We try to tinker and restore. We run in and salvage log it. We replant it with the late-successional species, such as conifers, and they grow very quickly,” says Crisafulli.

In the South, where many forests are grown for timber, researchers are discovering that some varieties of trees can tolerate natural events better than others. “There’s some indication that longleaf might be more wind resistant than loblolly pine,” ecologist Stanturf says.

But time heals all wounds, and the fierce forces of nature are nothing new for forests, governed by the equally powerful force of re-growth and renewal.

Freelance journalist Carrie Madren writes from northern Virginia.