The ongoing volunteer effort to create the midwest’s longest continuous hiking trail.

By Jerry Dupy

Frustration and outrage were the core emotions that led to two men’s decisions to take on abandoned trail-building projects in the wildest parts of the Arkansas and Missouri Ozarks. Frustrated with the half-hearted approach to local trail construction and maintenance, Tim Ernst formed the Ozark Highlands Trail Association (OHTA) to create and maintain the Ozark Highlands Trail in Arkansas. Similar outrage led his Missouri counterpart, John Roth, to found his own state’s Ozark Trail Association (OTA). Today, Ernst and Roth’s all-volunteer associations care for and expand these trails. The ultimate goal is to merge their trails at the Arkansas-Missouri border to create a 700-mile-long through trail from Fort Smith, Arkansas to St. Louis, Missouri. That Trans-Ozark Trail won’t become reality anytime soon, but it remains the goal as the two separate trails continue to grow toward one another.

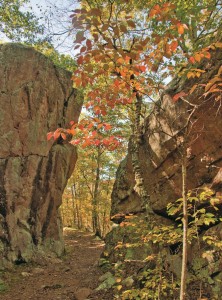

These two trails are well known among avid cross-country hikers, simply because they offer treks in some of the most scenic country found between the Appalachians and the Rockies. They traverse sections of two National Forests and the country’s first National River, and snake their way up and down rugged hills and “hollers” to scenic points that take one’s breath away.

Arkansas’ Ozark Highland Trail

Ernst explains how his frustration began to grow back in 1979, when he was working for the US Forest Service helping coordinate youth groups building short lengths of trail that essentially led to nowhere.

“I hiked each new short section as they were completed,” Ernst recalls. “One thing that was really odd—they did not build the trail up to a road. They would quit the construction 100 yards back in the woods so that the trail could not be seen from the road. They were actually hiding the trail, and didn’t want anyone to use it until the entire thing was complete—a really dumb idea!” Why would anyone go to the effort of building short, disconnected lengths of trails and make no effort to create trailheads?

“The result was that no one ever knew about the trail outside of the Forest Service and myself. I was the only hiker who knew about or used those first few trail sections,” he recalled.

Ernst said that it quickly became obvious to him that the Forest Service was not in the hiking-trail business. Trails Act funds, which had gone into the sputtering trail-building efforts in both Arkansas and Missouri, dried up and all new construction was halted by 1980.

“It became clear,” he said, “that the only way the Ozark Highlands Trail (OHT) would ever become a reality was if a group of volunteers was formed to do the work. The government wasn’t going to have anything more to do with it, so I got the group going, and the rest is history.”

“The rest” involved calling together likeminded folks for a meeting in Fayetteville, Arkansas, in the fall of 1981. He expected a few avid hikers to attend, but was shocked when more than 50 came, and they soon formed the core of the OHTA. Since that first organizational meeting 30 years ago, more than 3,000 OHTA volunteers from 22 states have given over 300,000 hours of their time to create and maintain a trail that runs unbroken from Lake Fort Smith to Woolum on the Buffalo National River, a total of 165 miles, all of it within the Ozark National Forest.

At Woolum, the OHT connects to the Buffalo River Trail, running alongside the Buffalo National River, a gem of a national treasure. Twenty-six miles of the Buffalo River Trail are complete, and OHTA and other volunteers are currently working with the Park Service on an additional 15-mile section along the river to help speed that project along. An “orphan” portion of the Ozark Highlands Trail runs through 31 miles of the Leatherwood Wilderness Area of the Ozark National Forest, and can currently be reached only by “bushwhacking” through a 15-mile section of another wilderness area.

Ernst oversaw most of the OHTA’s efforts as its first and only president, contributing more than 18,000 hours of his own time until he gave up the reins in 2009.

Missouri’s Ozark Trail

In 1997, St. Louis businessman John Roth was dismayed by the deplorable conditions he found hiking along the Trace Creek trail in the northeastern portion of the Mark Twain National Forest. He called the Forest Service to complain. The agency’s Paul Nazarenko was on the receiving end of that call, and told Roth that if he wanted to see a better trail, he could just come out and help fix it. Nazarenko recalls Roth showing up a day later, wearing loafers, looking like a “computer geek,” but ready to work.

Roth and a fellow outdoorsman, John Donjoian, figured out early on that the meager efforts of a ragtag band of trail workers weren’t going to get the job done. Not only did the many lengths of disconnected trails in southeast Missouri need to be maintained, but they would also need to be connected in order to create the Ozark Trail. Roth and Donjoian saw that it would take an organization of enthusiastic volunteers to create a lasting trail, and in 2002 Roth founded the Ozark Trail Association (OTA) with the mission to develop, maintain, preserve, promote, and protect the rugged natural beauty of the Ozark Trail.

Roth served as the organization’s first president, and began to craft a dream that the Ozark Trail would one day extend from St. Louis to Arkansas and rival the Appalachian Trail in popularity. Under his leadership, the OTA grew to more than 2,000 volunteers, fixing existing trails and building new ones to tie them all together. In 2008 alone, 500 OTA volunteers donated 13,300 hours of service, and were recognized by the Forest Service with a Volunteer Program Award. Roth was not to see his association’s work move forward. In 2008, he died in an accident on his farm in Steelville, Missouri.

The Ozark Trail now stretches from Onondaga Cave State Park in Crawford County, southwest of St. Louis, to the Eleven Point River in Howell County, just 30 miles from the Arkansas border. The continuous trail is now 230 miles long, and, in adding an important loop trail to the east and other spurs, the OTA oversees more than 360 miles of well-maintained pathway through these rugged Missouri Ozarks. The trail system is gaining popularity among a diverse group of folks: serious long-distance backpackers, families seeking daylong outdoor adventures, backcountry bicyclists, and horseback trail riders.

Working the Trails

Nature has a way of inexorably reclaiming its own. Foot trails, once established within the confines of a wilderness, are there only as long as humans continue to intervene. Without constant maintenance, a trail quickly fades into its surroundings, becoming littered by deadfall, choked by brambles and sprouts, and eroded by rain.

Both trail associations address this reality with their “Adopt-A-Trail” programs. By agreement, adopters promise to maintain a specific section of trail two or three times a year. During these daylong or overnight outings, groups of individuals, a variety of organizations, and sometimes whole families descend upon their sections with lopping shears, shovels, mattocks, weedeaters, and (for those certified by the Forest Service) chainsaws.

Roy Senyard, an OHTA board member who coordinates maintenance, works to keep the 81 sections of trail adopted at all times, and joins in to handle the big jobs when large trees fall across the trail. As hard as the work can be, it remains a true labor of love for Senyard, who retired to the Ozarks and just happened to discover a trail sign while on a drive through the country. He began hiking regularly and joined OHTA “just to give back for all it gives to me. It’s a never-ending job, but when a hiker passes you while you’re working and just says ‘Thanks for what you do,’ it makes it all worthwhile.”

In Missouri there are 94 trail segments caringly maintained by those who have adopted them. Ozark Trail president Steve Coates says of the labor-intensive efforts involved in building and maintaining trails, “The OTA provides an opportunity to give something back. Plus, it lets me express my love for the outdoors and for hiking. It is very satisfying to work side-by-side with a wonderful group of volunteers during a day of trail building, and then to enjoy walking out over the trail that we just built. It is rewarding to know that newly constructed trail will be something future generations can enjoy.”

OHTA PresidentWade Colwell echoes that sentiment: “There’s nothing more rewarding or satisfying than when you turn around at the end of the day and walk back down the soft path your efforts have created. You feel a definite afterglow.”

“I used to hike the OHT without any thought about maintenance,” says OHTA board member Jim Warnock. “I thought people were paid to do what little maintenance was needed. Boy, was I mistaken! When the section from Dockery Gap back to Lake Fort Smith was abandoned for several years while the new park was being built, I got to see just how quickly a trail could disappear. I continued to hike that section, did some marking and light lopping, and over time developed a sense of ownership. I came to love hiking that 4.5-mile section in all seasons, so when it once again became an official part of the OHT, I was able to adopt it.” Back in Missouri, OTA board member and “Mega Events” coordinator Greg Echele speaks of the bonds that working on the trail forms. “For some of us the Ozark Trail Association is like a big, productive family. Working and playing together, we have produced a remarkable outcome. We have constructed 43 miles of fresh trail, and we maintain 250 miles of existing trail with 700 paid members and 6,000 volunteers. This labor of love provides recreational opportunities for everyone who wants to enjoy the beautiful Ozark forest.”

Overcoming Challenges

In the past few years, the work of the volunteers in both states has been set back dramatically by natural disasters. A plague of red oak borers has taken a great toll on the Ozarks, although most knowledgeable observers now believe that the infestation is finally playing out. In the winter of 2009, a devastating ice storm felled or severely damaged Ozark hardwoods and pines by the thousands. Evidence of that damage is still visible, but the work to keep the trails clear goes on. If those disasters weren’t enough, a series of storms in the spring of 2009 caused some massive mudslides along the OHT that are still being dealt with.

Possibly the most amazing thing about these tireless volunteers is that most of them have day jobs. Ernst is a noted nature photographer and author. Colwell is an investment consultant. Coates is a highway planner and consultant to the Missouri Highway Department. The one constant among them is their glee when they leave their respective cities behind and head into the Ozarks’ most remote areas via the trails they have helped build.

As for the dream of one day connecting the Ozarks Highland Trail and the Ozark Trail to complete the Trans-Ozarks Trail, there is optimism it will one day happen, but major obstacles must be overcome.

In Missouri, at least 70 miles of the 100-mile corridor along the Meramec River from McDonald County to St. Louis are privately owned. On the south end of the Missouri trail, private land ownership stands in the way ofcrossing that final stretch to Norfork Lake on the Arkansas-Missouri border, and much of that property has been turned into pasture, making for a less natural landscape for hikers to enjoy.

In Arkansas, one of the OHTA’s challenges is a stretch through the Lower Buffalo Wilderness Area that would connect the main trail to the Leatherwood section. The Buffalo National River superintendent has nixed plans for an 18-inchwide trail through that area. Members say they are hoping, with a recent change of superintendents, this decision will be overturned. Finally, the OHTA hopes to connect with a series of trails around Norfork Lake that are being built by a different group of volunteers in the Mountain Home, Arkansas area with the assistance of the US Army Corps of Engineers. From there, the bridge that already spans the lake would be the final link.

Connected or not, these two trails offer some of the greatest opportunities in the Midwest to explore the natural landscape of an ancient plateau. For both the seasoned cross-country hiker and families just looking for a few hours in the mountains, they provide a unique chance to drink of what Henry David Thoreau called “the tonic of wilderness.”

Jerry Dupy writes from the heart of the Ozarks near the Arkansas-Missouri border.

The OTA and the OHTA

The Ozark Trail Association is based in Potosi, Missouri. Its website, www.ozarktrail.com, offers an extensive array of photos, maps, member comments, and a very good hike planner. Membership in the association is $20 a year for individuals. The group meets monthly, and sponsors several special events throughout the year. For a published overview of the trail, with detailed descriptions and photos of each section of the Ozark Trail, “The Ozark Trail Guide,” written by Peggy Welch and Margo Carroll, is available online at www.ozarktrailguide.com.

The Ozark Highland Trail Association’s website, online at www.ozarkshighlandtrail.com, gives details on upcoming events, current information on trail conditions, and lets you download a membership form. Dues are $20 a year, and the group meets monthly in Fayetteville. A comprehensive guidebook, “Ozark Highlands Trail Guide,” written by OHTA founder and longtime president Tim Ernst, is available at www.timernst.com.