By Katrina Marland

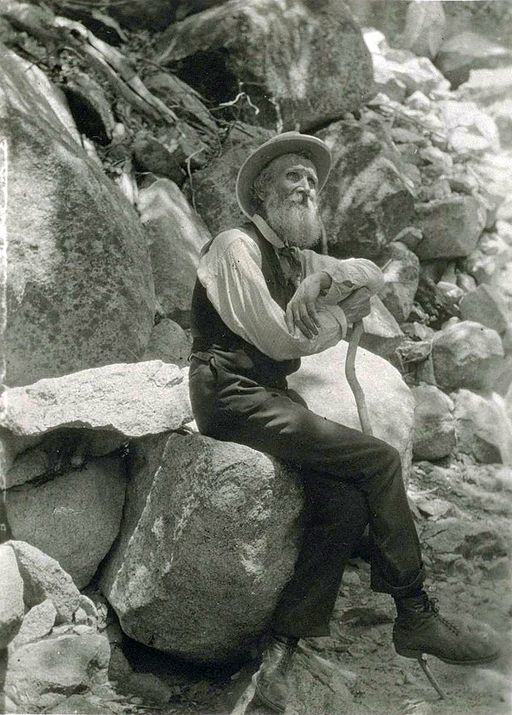

The conservation movement has been fortunate enough to have a number of truly wonderful figures over the years. Few of these people, however, are as recognizable a name as John Muir. This man was a naturalist, a writer, an adventurer and above all an advocate for wilderness. His work was so influential that many call him the “Father of National Parks.”

This Saturday is John Muir’s birthday — he was born April 21, 1838. So we’re taking a moment today to look just a few of the many places we still enjoy today, thanks to his work.

Yosemite National Park

In many ways, Muir was far ahead of his time in recognizing both cause — his theory of glaciation in the Sierra turned the theories of the day on their ears — and effect in the natural world. He strongly believed that one of the greatest threats to his beloved Yosemite was the continued spread of livestock. Though the area was owned by the state, the public used it as their own without concern for the forests or grasslands; sheep, goats and cows were permitted to graze across the region. Through a series of articles in the magazine Century, Muir advocated strongly that the lands be protected and never turned into grazing pastures. His writings eventually led to the 1890 act of Congress that created Yosemite National Park.

Mount Rainier National Park

At age 50, John Muir’s travels led him to Washington’s Mount Rainier. Along with several companions, Muir climbed the 14,410 feet to the mountain’s peak in what was only the fifth recorded ascent. He wrote about his experience in Ascent of Mount Rainier, which helped to bring the location into the public eye, and he became a strong advocate for the region, wanting to protect the area’s forests, meadows, glaciers and, of course, the mountain itself from development of any kind. On March 2, 1899, Mount Ranier National Park officially became the fifth national park in the U.S.

Sequoia National Park

This park is home to some of the most impressive trees one could ever hope to see, including the long-standing big tree national champion “General Sherman,” a giant sequoia and one of the largest living trees in the world. Muir walked through these groves of giant sequoias and thought them to be among the most fascinating of ecosystems — certainly worth whatever protection humans could afford them. He was a strong voice in preserving the area known today as the Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Park.

In his decades of working to protect natural places, one of Muir’s greatest and most valuable attributes was his eloquence, which poured through in every book, article, or letter he ever wrote. From his words alone, people could see the beauty of places they had never been and were willing to take up the cause. So it seems only right to leave you with words from Muir himself:

“Any fool can destroy trees. They cannot run away; and if they could, they would still be destroyed — chased and hunted down as long as fun or a dollar could be got out of their bark hides. … It took more than three thousand years to make some of the trees in these Western woods — trees that are still standing in perfect strength and beauty, waving and singing in the mighty forests of the Sierra. Through all the wonderful, eventful centuries God has cared for these trees, saved them from drought, disease, avalanches, and a thousand straining, leveling tempests and floods; but he cannot save them from fools — only Uncle Sam can do that.”

~John Muir, “The American Forests,” Our National Parks, 1901